Going global: Linda Peters on advising world leaders on the future

Linda Peters advises the US government, the United Nations and other world leaders on how to turn data into effective action and policies. From forecasting the timing and scale of catastrophic food droughts, to formulating strategies for the mass deployment of foreign aid, Linda Peters holds firm on the frontline, working to combat some of this generation’s greatest challenges.

At the height of the COVID-19 outbreak, Linda's expertise in data analytics and statistics came to the fore. Her work with the US Census Bureau on the first ever entirely digital Census took on new significance when the pandemic arrived and spread rapidly across the United States. Tune in now to hear Linda Peters bring new meaning to the term ‘data-driven’.

Never miss an episode of Directions with Stan Grant – subscribe now.

Featured in this episode

Get the latest from BGT Productions

- Click to view the episode transcript

Going global: Linda Peters on advising world leaders on the future

How can we ensure the data that matters is informing our actions?

Linda Peters: When you first go in and start looking at data, you don't know what you're going to find. You don't know if a certain data set coming from an entity, be that a utility company or a ministry of health, like how rich is that data? How complete is that data? How current is that data? So you're going to have to iterate through all of those different data sets and see, what's going to reveal the information and help you start to establish the patterns. As geographers we always look for patterns.

Stan Grant: In the age of the coronavirus and a global vaccine rollout, the accuracy and scrutiny of data has never been more crucial. Linda Peters is a world leading data strategist. She advises government leaders on how to turn data into effective policies that address some of humanity's greatest challenges. From deploying foreign aid during famines, to building sustainable infrastructure.

Her work with agencies around the globe, including the US Census Bureau, to create a digital Census, took on new significance as the COVID-19 pandemic arrived.

On Directions, you'll meet a leader, who looks for patterns in our ever-changing world.

Support for this episode comes from the country's leading mapping technology and services provider Esri Australia. To learn more about how Esri tech is supporting the world's most progressive leaders visit esriaustralia.com.au/trailblaze.

Hello, I'm Stan Grant. Welcome again to our Directions leadership podcast. This century really is proving to be all about a couple of things. It's about security. It's about privacy. It's about data. And of course, the way that social media has really shaped our lives and how much we are willing to give of ourselves. And of course, how that information is used.

We're going to be speaking to someone today who is an expert in collecting data and statistics and how they are used and how that impacts leadership as well. Linda Peters of course, is a leader in her field and works with governments around the world and the United Nations and I'm pleased to say is joining us here today on the podcast. Linda, lovely to see you.

Linda Peters: Thanks Stan, great to be here.

Stan Grant: There is that saying, and I know it's a well-worn one, lies, damned lies and statistics. And I think about that and I look around at the state of the world and how often in recent times we have been confounded by data and polling. Has that saying ever been more true than there are lies, damned lies and statistics.

Linda Peters: Yeah, it is true. And that there's actually a saying in the geographic world of how to lie with maps. Right. You have to make sure you're communicating the right message with your data. Not making it tell a story that you just want to say.

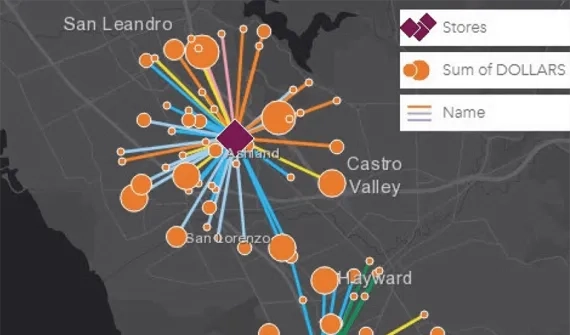

Stan Grant: Yeah I'm really interested in that actually. You talk about geography and data and how to lie with maps. What do you mean by that?

Linda Peters: When you bring data together into a map, it's a great way to visualise statistical data. But a lot of people don't know how to visually interpret information, right?

Statisticians could look at a map immediately, a thematic map of some type, and be able to tell you the patterns that they see in that. But the average citizen may not be able to, or the average legislator. So we need to find ways to help people.

Stan Grant: And when you do something like that, when you take data and you, you apply that and you map that, you can also get a snapshot of a place or a people, or a moment that may tell you something. But the danger I would imagine is in thinking that it tells you everything.

Linda Peters: Yeah, you need data from a lot of sources to get the whole picture. And of course, that was brought home to us very clearly during this time of COVID when things were first breaking out, as we saw, you know, all the ministries around the globe, statistical ministries, health ministries, education ministries, all trying to come together to bring that information together so we could get a full picture as to the situation.

Stan Grant: Yeah, you've raised COVID, I was, I was going to come to that a bit later, but let's just dive in because that has reshaped our lives. And of course, so much of this has been about how we use data, how we use statistics, what are the chances of getting it? What are the infection rates, how contagious it is, what are the death rates?

And we're learning about this as we go. As we find out more about it. As we have more cases, we learn about the level of fatalities, who that's affecting, and yet we're having to make decisions aren't we on the run, in real time decisions that have an impact on people's lives far beyond in fact, the impact of the virus itself.

Linda Peters: Well, there's another old saying, don't let perfect be the enemy of good. We've got to make decisions with the information we have at hand. You know, in a week from now, we might have more refined information that that's a closer percentage and accuracy, but we maybe don't want to wait that week to make that decision because that could impact a lot more lives.

Stan Grant: I mean there's been such a different response to it in different parts of the world, but have we been guilty of looking to have a perfect response and that being the enemy of the good and conversely, have others, and we've seen this particularly in the United States, which has been devastated by it, perhaps did not respond as quickly to the data as it could have.

Linda Peters: Yeah, potentially. And here in the US as we look across the different States, you'll see States reporting in at different levels. And I get this question all the time. Well, how accurate is the data? You know, how is the reporting coming in? Is there under-reporting in the hospitals or over reporting. Perhaps there is, but there's also the mitigating factor of once you put all that data together with the precision level of the data is higher.

So again, we've got to make decisions with what we know now, we don't have that rear view mirror. So we've got to cross that.

Stan Grant: And of course those decisions impact as I say, people, far beyond the virus itself, I mean there are people who may never get it, and if they do get it, we know that statistically at least, 98% of people, roughly of what we're seeing in now will be fine.

Many will not even know they have symptoms. But of course, everybody has been affected to some degree because we have had our freedom curtailed. We've seen our economy shut down. There's been massive job losses and an economic recession, if not a depression. Using data, what to listen to, how to make decisions.

How do we do that? Uh, particularly at a moment of crisis like this.

Linda Peters: Yeah, sure. And I'll come back to our US census agency who I think has done just a phenomenal job during this time, because, they began to react immediately, doing some what they call pulse surveys, to get a pulse on what was going on within the household, but also to get a pulse of what was going on in our economy right?

So to your point, we have to understand the economic impact. The jobs impact, uh, across the nation, at a granular level, but in near real time, right? Again, this is where we can't look to be perfect. We've got to move quickly and collect that data. But we also have to look at information on how families are being impacted. Parents with young, small children are at home, and having to homeschool. Well, okay, that's one challenge in and of itself. But what about those rural areas where we don't have connectivity? If you don't have the internet, you can't homeschool. So now we need to be able to bring in that additional layer of information and raise all of that up to the decision-makers to the policymakers to take action on.

Stan Grant: And mapping is critical, I mean, you've just talked there geographically. You've talked about California. You've talked about the hinterland and rural areas. And we know that cosmopolitan, metropolitan areas with lots of traffic, people coming and going have been disproportionately affected. We also know that poorer communities have suffered, African American communities in the United States have suffered, but around the world we see the same patterns.

And then there are often rural areas, which may not in fact be that effected at all. And yet are dealing with the same policy response. So it does come down to, again, that ability to map effectively and then make decisions, based on not just what the headline data is showing you, but what the qualitative information is telling you as well.

Linda Peters: Right. And being able to interpret that data, because if I were to take all these different statistical layers that I'm talking about right now, and just push them over in a piece of technology to a policy maker sitting on the Hill, they wouldn't be able to understand that. So, we do need to be able to be storytellers as well, and to be able to walk them through the data.

Stan Grant: I love that you've gone to storytelling because I, I really think, if I think about leadership, in any form, but particularly I think political leadership or leadership during a crisis, it is about being the most effective storyteller. How do you turn that into a story and accept the fact, which is not always easy for everybody to accept the fact that yes, you are a leader?

Linda Peters: For me, I work with national statistical offices in countries around the globe. A statistical agency isn't there just for the sake of creating data, but data for decision-making. So how do you teach them how to apply this technology? And a great example of that is around the sustainable development goals.

So, you know, before we all knew what COVID was, we were focused on sustainability, right? We all know the world has a lot of problems and things we have to fix.

Stan Grant: And in many respects COVID is now folded into that. That is part of what we're facing. Yeah.

Linda Peters: Very much, very much so, you know, as we think about the different goals, targets and indicators, how do we take all of the vast amount of data that's needed to solve the different problems from education to food security, to climate change, biodiversity, and put those together in one system where people can understand that.

So it's having frank conversations around things like that, that I think really help.

Stan Grant: Drawing on what you've said, the quality of the information you have, the ability to turn that into a story, the ability to educate, to listen and to build trust and ultimately, to act and to give people the confidence to act. Our hypothetical, you mentioned that you do some work in Africa and our hypothetical begins in an East African nation, that has become the focus of humanitarian groups across the globe.

Now, the country has not done a census since 2006, and there are a number of reasons for that. There's a lot of political instability in the country. Uh, and not a lot of money. To compound this, the country is really growing, very very rapidly. Data that you have today is out of date tomorrow. And without this, it's so difficult for people to be able to respond. The country now faces this reality.

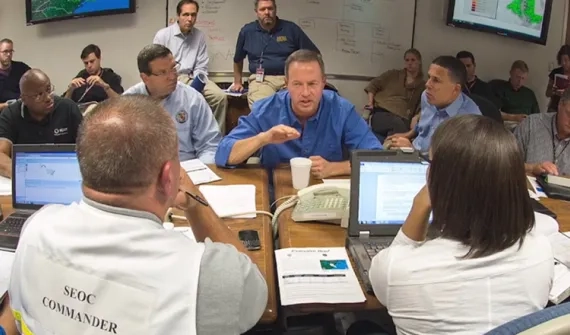

There is a national emergency, humanitarian crisis. 90% of people are living in poverty in rural areas. Now there's been a major flood, that's inundated parts of the country. And of course, all of this set against COVID-19 pandemic. You arrive there now, you've been called upon to go in there and to brief a UN delegation that will help to guide and support the authorities in the country to be able to deal with this multi-layered crisis.

What do you immediately do when you touch down? The first meeting you have you walk in there, the place is in crisis and they're looking to you to say, what can you tell us now to make the right decisions? Where do you start?

Linda Peters: Yeah. Um, well, there'd be a couple of key ministries that need to be in the room. One of those is the national mapping agency.

The other one is the national statistical office. Without them, we can't begin to do any analysis. We also are going to reach out right away to imagery providers and get some of that real-time imagery. You know, there's so many of the birds up in the sky, so we're going to pull that imagery data so we can start to do some modelling and interpretation, population estimation modelling.

Because if we don't have current data. There's no sense in looking at 2006 data, let's look at the satellite imagery, earth, observation data. We can interpret that using some tools and we can start to overlay other data. So we're also going to reach out to other agencies across the country to bring in other information sets that could be useful.

Things like utility information, transportation, layers, right. We want to understand the infrastructure of the country because what you're going to have to deal with is, how do I manage the response? How do I set up my supply chain network? Because I'm going to have to move water and supplies in, and I need to know where I need to do that.

And so, without being able to have a map, not only of the terrain, but where the people are, I can't begin to start that planning process.

Stan Grant: Linda, I can see why you were so good at that, the way you've walked in and the way you went bang, bang, bang, bang. This is what we're dealing with. These are the gaps in the system.

This is where we go for the latest information. You're hitting the ground running. But I want to go to that idea of, okay there hasn't been a census test since 2006, information is out of date, and are you getting into, I know you can estimate, I know you can try to extrapolate from the information that you have, uh mapping and imagery, but it's accuracy isn't it?

How confident are you in being able to make those assessments based on information that you really don't have?

Linda Peters: If you can use the earth observation data like that and get to say a 95% accuracy rating, you've identified at least where the settlements and the villages are, because if I have 2006 data, I can guarantee you there's going to be a lot of new villages that don't even show up on there.

And in fact, that was one of the problems that the Gates Foundation faced with the polio crisis across Africa, particularly in Nigeria, that there were just new settlements that they didn't even know existed. So you can't eliminate a disease, unless you know that you're getting to and inoculating, all of the people to, to prevent it from spreading.

I may not be a hundred per cent accurate, but if we can get out to those settlements and as we start to set up the supply chains and to distribute the food and the water supplies and things like that, well, then we can be continually refining our information, because everybody's walking around with a mobile device in their pocket, and we can be collecting real time data from those devices as well, those cookie crumbs, if you will. And they can be capturing information while they're out there dropping supplies as well saying, there's a village here, we haven't gone there yet. We need to come back here tomorrow.

Stan Grant: Here's the problem. You've got the information and you said you want to get out, but the government doesn't even want you there.

They have reluctantly accepted the pressure to allow the UN in, and you have to go in there and you have to tell them that you need to do this. And this is for the good of the country, but you're meeting this resistance. How do you do that? How do you build that level of trust in real time, meeting a level, frankly, of hostility?

Linda Peters: Again, it comes down to having those frank conversations and talking about the data. Showing them how you can bring this information together that will give them a view into what's going on in the country. Anyone in a humanitarian crisis like that wants to do the right thing. So I think if you can show them how it can work, then that's when they'll be willing to accept it.

Stan Grant: The last thing they want, the government wants, and the leadership there is for any outside agency poking around in things that may cause problems for them. There've been allegations in this country of corruption. We know that it is a very poor country and they're worried that if we let these people in and they start fishing around, they're going to find things that are a problem for us.

At this moment, do you have to set aside some of those other concerns? Do you have to accept, and going back to your idea that the perfect cannot be the enemy of the good, you're going to have to deal with some pretty unsavoury characters and some things that absolutely appal you. And yet you are there to deliver a humanitarian response to people, who were not part of the system, who were being ripped off by this system.

Do you have to park something to be able to get the job done?

Linda Peters: That's not why you're there. If you're there to do this humanitarian aid and to make sure you're setting up a supply chain and a distribution system so that the country has food, safety and security. That's your primary mission, right? You're not going to be able to to, to fix all of those other things that are going on.

And so that's also something that you can offer to the country that, you know, we're coming in to help. We're going to help you understand how to do this. We're going to teach you how to do it yourselves while we're here.

And we're going to leave everything that we create behind. It's your asset. It's your country.

Stan Grant: Here's another problem. It is an inherently male culture. While there is suspicion of outsiders. There are some issues there that they would rather keep hidden. There's also the fact that you're coming in there and you're telling an all-male leadership, what to do, and you're crossing some cultural boundaries, and you're confronting a chauvinism that maybe you don't confront elsewhere. How do you deal with that? And I'm sure you've got experience to draw on, to have to do, to deal with these situations.

Linda Peters: I do. I do, and, and again, it's about respect. I understand, you know, cultural norms. You have to in, in the role that I'm in, because again, I work with countries all around the globe, Africa, Europe, Asia, Latin America. So, you have to do your homework and know something about the people, their culture, and what's important to them and bring that into the conversation early on.

So they know that you have bothered to take the time to understand them and to understand what's important to them. I do come from a different society, right? I live in the United States. It's a Western culture and it is different, but hopefully my credentials also give me the authority to talk about the subject and that is not threatening to them from a cultural respect.

Stan Grant: And you've also raised something I think that is fundamental here and that is that, information does not come in a vacuum. It is informed by its own prejudice. It is informed by the way that information is collected. The questions that are asked. Who is prioritised. All of those things feed into this as well, so how do you extract that value judgement from the information that you were seeking?

Linda Peters: Yeah, that's, that's really an iterative process. You know, when you first go in and start looking at data, you don't know what you're going to find. You don't know if a certain data set coming from an entity, be that a utility company or, a, a ministry of health, like, you know, how rich is that data, how complete is that data? How current is that data? So you're going to have to iterate through all of those different data sets and see, what's going to reveal the information and help you start to establish the patterns. As geographers we always look for patterns.

Stan Grant: We know we are dealing with a country and we've worked through some of the cultural issues, with some of the political issues, even potentially some of the legal issues in the country, but you're dealing with a place that has multiple crises. It's a perfect storm here. It is poor. There's been political instability.

There's been conflict. You've got COVID set against a whole range of other chronic illnesses that are of long standing in the community. And now you've got this devastating flood. Is this a situation where you have to triage, a situation where you need to prioritise. And how do you do that? What is the immediate priority and what is the long-term plan?

Linda Peters: You know, the initial ideas would be looking at your most at-risk population. So where are the seniors? Where are the women and small children? where are the disabled? Where is the extreme food insecurity, water issues? And then moving in very quickly into the health and safety issues. So from a, a health care perspective, looking at that network, understanding where you have hospitals, where you have clinics and where you have doctors and nurses, you know, midwifery, things like that. You're going to need to look at all of those things, pretty quickly together.

Stan Grant: And now you're at the point where you've delivered that information. And you have, you have to now let go, at what point do you walk away and trust in the decision-making.

Linda Peters: It's their decisions to make, right? Not ours, but, uh, what we want to do is make sure that they understand how to be able to continue to bring more information into the system, how to be able to publish data out, how to be able to get a report, a map, some sort of information product that's going to be useful out into the hands of either the policy makers or even thinking about citizens.

So, once I know that they know how to do that and publish data and services, and we can see that, that process will continue, then we can set them off, right? We've taught them how to do their work.

Stan Grant: Okay. Job done. You leave and, and they, they get onto it. We'll see how successful they are.

Now it's worth letting our listeners know, if you want to learn more about some of the amazing work Linda has been undertaking with United Nations and other groups. Get along to our website at directionspodcast.com.au.

There's a great story map of how the UN is tackling gender inequality and another one on climate change. There is also a link to a free trial of the software Linda uses in this important work.

I want to go to the question of how information is used in our world. And we've seen things like Cambridge Analytica, we've seen allegations of meddling in elections. We know that we’re been tracked constantly. Now you are someone who can be seen, frankly, as the enemy here. How can we trust you Linda? You mentioned trust, but you're, you've got a lot of stuff on us, you know, potentially you and others like you have a lot of stuff on us.

Linda Peters: And again, that's part of the conversation to educate about how much information is already out there.

So it's not that, um, Linda is trying to collect information on you, but rather I'd rather show you all the information that's out there and help you understand how to either make sure that information stays secure, or, to understand the risk around that data.

Stan Grant: But Linda you can be used. This is the point, right? You can be used by others who don't come to this, perhaps with the same ethical standards that you may have. You're collecting information, but we know in the world that we're in right now, politicians, other untrustworthy unscrupulous actors, can use that information that you gather and use it against people. How do you feel about that?

Linda Peters: Well, I think the thing that you have to do about it again is understand how we can use the data for good. I don't think we can turn the clock back, you know, Facebook, Twitter, things like that, they're not going away. Yeah, you know, even if they have hearings and they decide to break up some of these companies, there'll be new things that come around and get reinvented right. When I was a young professional, I worked for a company here in the US that was known as MapQuest. It was a big deal because it was the first-time digital maps of the whole country were available on the web. And at that point in time, I distinctly remember getting phone calls. You know, it'd be a 70-year-old woman from South Florida calling and saying, you don't have my house right on the cul-de-sac. It's on the wrong side of the street. You need to fix it, right.

People were looking at that at that point in time as being invasive. And yet they wanted to correct the information. I don't think we can put the genie back in the bottle and I don't mean to be flippant, but it's going to continue. So how do we best manage that? And how do we use data for the good?

Stan Grant: But we have to, we can't lose sight as well of, of a moral viewpoint of this. We can say the genie's out of the bottle, but we live in a world where we need to make ethical decisions. Does this make you angry that your work can be misused or what about the morality of a lot of this?

Linda Peters: Well certainly I want to see the work that we're doing, being used for the right purposes. Um, I'm not sure I can control that.

You know, when we create base data, whether that's, uh, information on soils or, or some other component of say the physical geography, um, someone might use that for their own cause, you know, a means to an end. I think that what we see though is for the most part, most of the users that we're working with are using this data for good, right.

They're using it in citizen science and looking at biodiversity and looking at exploring the oceans and, um, you know, looking at issues of conservation and humanitarian crisis.

Stan Grant: Well, let's go back to this idea of the genie being out of the bottle too, and where it's taking us, is this the handmaiden of demagogues and authoritarians, I mean, we know that the ability to map a community, the ability to quantify communities and say, this is a white working class, or this is a black community or X or Y. And then the ability of politicians to exploit the fear or anxiety around this as well. How do we deal with this?

Because right now in our world, that political populism has really taken root and it is most definitely geographic and demographic at its source.

Linda Peters: Yeah, definitely a challenge. I think the efforts we've seen here in the US and in other countries around what's called differential privacy, or disclosure avoidance are going to be key.

And this is again where it comes to understanding the data, how to secure the data and keep data private. So, you know, every statistical agency collects data at the household level. Right. That's pretty personal. But you can't disseminate data at that level, if you want to keep the individual's privacy.

So then you have to understand how best to disseminate information, still have it be accurate and be sensitive to the individual rights. Those are not easy things to do together, and that is a lot of scientists and statisticians that have been studying this for the last several years and putting forward new methods for us to be able to do that.

Stan Grant: Are we redefining what the word privacy means now, I think about social media and I'm not an active participant in this but my children certainly are. And I'm very mindful of what they say about me, what they disclose about what we do, where we live. When you look online and someone's showing you what they're having for dinner and who they're with.

And if they're at the beach and what they're wearing or not wearing, frankly. This whole area now of, of what is privacy, it was something we guarded, but is it something now that we are absolutely willingly giving up.

Linda Peters: Well, I think in some cases, the answer to that is obviously, yes. I think we're also learning. I remember early on with social media, when a lot of people were posting about plans, where they were planning to take a trip to go here or there.

Well guess what the criminal element was very interested in that information of knowing when you're not home right. So we've learned, I think, you know, not to post that kind of information. So I think that gets more to your point is, you know, part of it is us understanding the risk and the position that we're putting ourselves into.

And part of it is, what is the benefit of sharing that information. And I think there has been a bit of a generational shift, right? If I look at, you know, my own nieces and nephews and things, you know, that are in their teens or early twenties, they definitely have a different mindset about it than you or I do.

Stan Grant: Yeah, and perhaps we will get to a point. well we're getting there, of self-correcting as well, that this is something that you get into self-regulation, which may be more effective than any government intervention or regulation as such.

Linda I wanted to just touch on before we go about, about leadership and what you bring to that.

Being a leader, it does require certain qualities. What do you bring to that? Because you're, you're a leader, you're a leader in your field. You're confident, you get in front of people. You stand there, you present information. You are integral to decision-making. What do you bring to leadership?

Linda Peters: I think one of the things that I've learned is that you have to treat people with respect. It's not actually about managing people, but managing the work, and how you can bring a project successfully through. As I said before, you know, that that trust component is really important. I think the qualities that I bring are that I am dedicated. I'm not afraid to tackle the task.

I'll go at it with confidence. I'll admit if I'm wrong or don't understand something and need to bring in other people for help. You don't have to go it alone. So to leverage that team around you, those are all important qualities that I see in good leaders. The other thing I would say is I sort of think of it as the three Cs.

The critical thinking, think about what it is that you're trying to accomplish, and then make sure that you can be innovative or creative in that work and that you can communicate and get other people to get excited about what it is that you're trying to do.

Stan Grant: Is it different for women, do you think? I mean, we still live frankly, in a world where most leaders are men and you can see that around the world. Is it different for women and in what way?

Linda Peters: Well, as a woman, I can say, I always think that women tend to work harder for it. Um, you know, I, I grew up in the seventies, so, uh, I've seen a lot of change here in the US uh, with the way that women are perceived in the workforce. And there there's certainly much more opportunity for women overall and particularly in the GIS community. I think we were very much ahead of the curve and bringing women into the discipline, into leadership roles and management roles, but we've still got a ways to go for sure.

Stan Grant: Yeah and when you talk about a way to go, what is the end game here? I mean, if you think about male leadership, it's so normalised, women are still judged by male standards of leadership.

I mean, you even see this in world politics you know, they look at someone like Angela Merkel or Jacinda Ardern in New Zealand and immediately they'll compare her to a male leader. And during COVID we've seen this, you know, there's been discussion around whether countries led by women perform better and what qualities they may bring.

What is the end game here when women are not just compared to male leadership, but we look at women who can be, have all the characters, characteristics that we may admire in, uh, in, in male stereotypical male leadership, even aggression. Certainly assertiveness, but also other qualities.

Linda Peters: Yeah. Judge people on their merits, not against another person right. Uh, how, how do you understand who's doing a good job and judge them against those merits? Um, you talk about the politicians. I did a study with the UN women in statistics, and we did some story maps around, uh, the per cent of women in politics globally. And it was really interesting because even here in the US where we think, Oh, we're, you know, we're we're doing well, we're ahead of the curve, the numbers aren't so hot.

And if I look at some other places like Rwanda stood out, I went, wow, look at this. You know, how is this happening in these interesting places around the globe where you're seeing female leaders emerge. And yet here in our own country, we're, you know, supposed to be more advanced and forward-thinking, we're still struggling to have an equal balance of women across our own Congress and Senate.

Stan Grant: Yeah. You've been really generous with your time and I wanted to finish on a bit of a personal note. I think a lot about statistics and I think about the narrative that is associated with, with that sort of information and how that can be liberating and it can lead to better decision-making, but it can also close in around you and it almost becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

You know, I sit here talking to you today and I'm an indigenous Australian and statistically if I looked at the data around who I am, people I come from and my family, I shouldn't even be here. Statistically, we die 10 years younger. We are 3% of the population and we're 30% of the prison population. All of the socioeconomic indicators we are lagging in, and yet I've come from that background and I am here and at least socioeconomically secure and stable, and I've had an interesting career. We can confound statistics and when you talk about the story, how do we take information, we map information. We look at communities and we make decisions and we need to make policy decisions, but we also allow for people to defy these statistics.

Linda Peters: That's the challenge, right? With that's the promise also of getting this information out there, getting the data open and having citizens and civil society become much more engaged in the conversation right? In years past, if we went back to 1980 or 1990, you know, when that census data came out, you know, as a young college student, I went to the library, right.

And pulled that big, heavy book out of the shelf. It was really hard to get to any information to make a decision. If even if I wanted to take something to my own little small town mayor to bring up a point around something that I thought needed to be fixed, that was really difficult to do. Today because we can make that information not only accessible, but usable, and we can make it open, you know, perhaps we're making it easier for us to make a change overall.

Stan Grant: Yeah and it's about that storytelling, isn't it, rather than trapping people in a, a deficit narrative, because these statistics may indicate disadvantage, people are not trapped there. And, and you said before that idea of, of that into better decision making that unlocks people's potential rather than traps the men in statistics, it is the storytelling I just keep coming back to this. You're, you're so right about that aren't you.

Linda Peters: Yeah, I think so. We, we see it happening. We see it happening here in small communities, you know, across our own native American populations right. You can't begin to make a change until you reveal the problem.

Stan Grant: Yeah. It's just been really fascinating. Fantastic to be able to talk to someone who's, you know, I work in the, in the world of words and journalism and the world of numbers is so foreign to journalists believe me, we're the ones who failed maths. It's great to be able to sit here and have this conversation with you, Linda Peters, thank you so much for joining us.

Linda Peters: Thank you again, Stan. It's been great to talk with you.

Stan Grant: And for more on Linda, her work with the United nations or to check out the mapping tech she uses to sort data and uncover the insights that really matter. Visit directionspodcast.com.au.

On the next episode, each time you use your mobile phone, you leave a trail behind. Each app you've used, every browser you've opened each link you've clicked leaves a digital footprint. The ethics of data, Dr. Amen Ra Mashariki on balancing knowledge with utility.

Amen: Government should not take on all of the burden of driving ethical use of data, but there is a role in terms of regulation and policy that government should have. But then we should also push some of that burden onto the communities or rather the community members in our respective regions, whether it's the UK, whether it's US, whether it's Asia, should stand up and also take its rightful place in this conversation and sort of lead thinking on how to be more ethical.

Stan Grant: That's the next episode for this season of Directions, this is a Boustead Geospatial Technologies Production. This episode was narrated by me, Stan Grant and Linda Peters.

Sound engineered by Nearly Media and Deadset Studios, with editing support from Kim Douglas and Sydney Podcast Studios. Artwork by Superscript, and our Executive Producers are Alicia Kouparitsas, and Raquel Jackson.

If you like our show, please give us a five-star rating. Leave a review and be sure to tell your friends. Follow us on Apple podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also download a free trial of Esri software, check out our show notes and access other resources at directionspodcast.com.au.

The views and opinions expressed in this podcast are solely those of the participants and do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of Esri Australia it's subsidiaries or partners. Hypothetical scenarios presented as part of this episode are purely fictional. And while they may draw on current issues, they do not depict the actions, values, or beliefs of any specific individual and or organisation.

And finally, this production would not be possible without the support of Esri Australia.

VIEW TRANSCRIPT

VIEW TRANSCRIPT