Criminal profiler Mike King shares lessons from the thin blue line

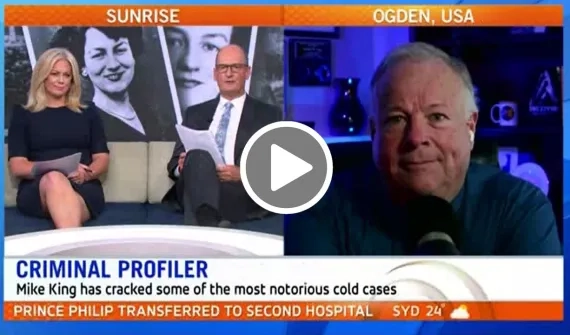

As one of the world’s leading criminal investigators, Mike King is intimately familiar with high-pressure life and death scenarios. For 40 years, he’s worked with law enforcement around the world, taught top police investigators the art of criminal profiling, and consulted on public safety strategy for large-scale events including SuperBowls, marathons, G20s, and the Olympics.

Never miss an episode of Directions with Stan Grant - subscribe now.

Subscribe to hear how other leaders are using cutting-edge mapping tech to solve global challenges.

Get the latest from BGT Productions

- Click to view the episode transcript

Mike King: “You know guys like you and me we don't know what it's like to fantasise about killing somebody, but we certainly know what it’s like to fantasise about being successful in our careers or other things.

So, we can vicariously begin to understand, because what we found is these serial predators are in pursuit of legitimate kinds of needs, but the difference between them and you and me, is that we go about it by the legitimate ways.”

Stan Grant: Arriving at a crime scene to sift through evidence is not for everyone. And neither is spending time with hardened criminals in high security prisons. But Mike King is curious. He's a leader who likes to think differently and to question and test the accepted facts. On Directions with me, Stan Grant, you're about to meet one of the world's top experts in criminal profiling, violent crime investigation and solving cold cases.

Disclaimer: Support for this episode comes from the country's leading mapping technology and services provider, Esri Australia. To learn more about how Esri tech is supporting the world's most progressive leaders. Visit esriaustralia.com.au/trailblaze.

Stan Grant: This is Directions and I'm Stan Grant. Many of us – including me – have a macabre fascination with crime. Who commits crime, who are the victims of crime and how crime is solved. In particular, how crime is solved in the world today where policing moves at such a rapid pace and where technology has changed our lives in incredible ways. It's a long way from Arthur Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes.

Mike King is a top cop. He was awarded national police officer of the year in the United States. And even once stopped a threat against President Ronald Reagan. He's now a leading crime expert and has led an innovative program to help authorities get inside the minds of criminals.

For example, he took mass murderer Dan Lafferty off death row, and escorted him around the country to talk to police officers about the criminal mind of a serial killer. This killer would answer the questions of investigators. It had never been done before.

Mike King, it's great to speak with you.

Mike King: It is my pleasure to be with you, Stan. I am so appreciative of the opportunity.

Stan Grant: Well the honour is mine and I've become a devotee of your podcast, which has been incredibly popular. And we're going to come to that, but I really want to start with that macabre fascination that we all have. What is it, do you think that draws us to crime?

Mike King: It is so strange, isn't it? And we find it especially with women there, there's this real fascination with serial killers and homicide and we think to some extent it's because there's probably more of a concern of being victimised themselves.

But for some reason that seems to be the group of people that are most interested in true crime stories. In fact, 98% of the people that listen to our podcast are women. And most of those have incredible backgrounds. I mean, it's a group of people that cover every demographic, every financial background, every socioeconomic situation, but it primarily ends up being women.

Stan Grant: Did you share that fascination yourself? Is that what drew you to law enforcement?

Mike King: You know, actually I remember I was a young man troubled to some degree in high school. I was playing American football and a Salt Lake City police officer who was assigned to our school actually befriended me and kept me from making some really poor choices. And I was so impressed with him and the things that he stood for, that it became a goal of mine to one day become a police officer, and I've now spent a lifetime doing it.

Stan Grant: Now I know that you're very modest about your achievements and about your career. But I did want to ask you about your own personal struggle to become a police officer because it almost didn't happen.

Mike King: Gosh, you have done your work? Yes. I mean, I truly did want to be a police officer. I was hired and within the first couple of weeks of becoming a police officer and I'd gotten through the training program. In those days, the training program was a couple of weeks riding around with an experienced officer, and then they turned you loose.

And sometime within the first couple of years, you were expected to get to the Police Academy. So oftentimes we had really under-trained people out performing a job. And you think about this job of law enforcement, especially in the States, it requires more education and more experience in the United States to be a barber than it does to be a police officer. And that's really frightening when you think about handing some 21-year-old testosterone filled kid, uh handing him a weapon and the authority to go out and take custody of people or to execute lethal force if they ever had to. It's really shocking in fact.

Stan Grant: So, how did you navigate that journey, and what did you have to overcome to reach those goals?

Mike King: I think number one, I've always been one who has focused on mentors and I've looked at the people who I thought were successful and it wasn't the hothead that walked around and flexed their muscle. It was the investigators that were just top notch. The administrators who actually administered and yet they stood behind you and they provided the top cover that you need when you're out in the field as a young officer learning the ropes. And as I focused on those role models, it became pretty easy for me to choose how to do things. There's an old saying we used to call the unwritten order of things.

And by watching those who are successful and just doing the things they do, you're going to just naturally end up having some successes in your life. And I just feel like the mentors I had made a huge difference in my life.

Stan Grant: One of the things that fascinated me and impressed me, particularly I learned from your podcast, is the way that you sought to empathise with the victim, the dignity of the victim. Even to the extent of going back and not just retracing the steps, but trying to inhabit the life of the victim as a way of being able to try to understand the crime and who may have been the perpetrator of the crime.

Tell me about that.

Mike King: You know that was something that I think all along I've had this love of people, number one, and that's really guided me. But the thing that I learned early on, Stan, was that instead of showing up at a crime scene and having that first question which I think we all have – which is the ‘who dunnit’ – instead we should kind of draw back a little bit and say, who is this victim and why did they become a victim?

What was it that put them in this location? What kind of decisions did they make in their individual levels of risk that they were willing to accept? Or were they just compelled to become a victim because of circumstances outside of their control? But as we start to understand who the victim is, it becomes a little easier to understand who the offenders might be from these huge pools of possible offenders.

Because that's really the challenge of an investigation is – to look at all these possibilities and sift it down, like an old gold panning person out in the Yukon or working a river to take all of these nuggets of information that are hidden inside of soil and water and everything else, and continue to sift it until you get those golden nuggets that tell you here's the most probable person for this kind of crime.

From that point it becomes almost mechanics to get confessions and other kinds of things because you've learned so much about the victim – the victimology we call it or this study of the victim – and then the suspect or suspectology.

And so, it really becomes important when we look at criminal cases to think about the victimology first and foremost.

Stan Grant: But you've also got to then put yourself in the minds of the perpetrator and some of these, of course, very violent crimes. What does that do to you, to get inside the mind of someone who could carry out these acts? And I would imagine it is difficult to separate yourself from that as well after a while.

Mike King: Yeah, I think there are some demons that hang around in your memories when you look at those kind of horrible events over and over again. And one of the challenges you have when you look at a case from a profiler’s perspective, is that you oftentimes are not there when those things happen or shortly after. It could be months or even years later before you see it.

But if you have the opportunity to go in and just sit in a corner in a house, for instance, where there's a homicide that's occurred and try to just stare at each individual wall one by one and think about what are you seeing? Are there bits of blood on the wall or are there pieces of evidence to tell you something?

Is the thermostat turned up too high? Are there ice cubes sitting on the counter that are half melted? All of those things start to teach you a little bit about the behaviours of what are going on in these crime scenes.

And then you kind of have to vicariously roll in the dirt and think about, if I were the offender, what would make that so specific or so important in the commission of – or the successful completion of – this particular crime. Guys like you and me we don't know what it's like to fantasise about killing somebody, but we certainly know what it’s like to fantasise about being successful in our careers or other things.

So we can vicariously begin to understand, because what we’ve found is these serial predators are in pursuit of legitimate kinds of needs, but the difference between them and you and me is that we go about it by legitimate ways – they go about these legitimate needs and accomplishing those by illegitimate means.

Stan Grant: And let's be specific about very, very dark cases – Richard Ramirez, for instance. I think you're involved in that investigation the Night Stalker. Tell us about that.

Mike King: Well, I didn't investigate Ramirez's cases but because I was doing a number of studies for the US Department of Justice, I went to the prison and met with Richard and talked to him about the way he selected his victims, how he committed his crimes, how we got away with those. But most importantly, I also wanted to know what that process of a psychopathy was in his mind. How he could lack empathy for these human beings that he’d tortured and taken the lives of?

And so, as you go through that process, you really begin to understand – because at this point, Richard Ramirez wasn't trying to keep from being arrested. He was on death row in San Quentin prison. He was in a position where he could really teach. This seems so strange to say that. In fact, I remember sitting down to eat prison lasagne – which is always one of my favourite things to do, Stan, is to get with an inmate and just have lunch with them in the commissary and talk to them.

And as I walked in, he was on one side of this metal table I was on the other and I said, “please sit-down Richard.” And he said “no, no, you please sit down”.

Stan Grant: That's unnerving, isn't it? That sounds like silence of the lambs or something, you know? I mean, that really is unnerving.

Mike King: Oh yeah. Incredible experience.

Yeah. But what it did is it taught me his level of control and how he escalated to maintain and manage that control. And then at the point you voluntarily give that control up to him because you want to be the student. You want him to teach what he thinks and how he perceives things.

Stan Grant: And as you say there, these people that we can imagine as monsters and who do monstrous things can be entirely charming in some ways.

And maybe that's part of the modus operandi.

Mike King: You know, it is interesting because if you listen to news reports whenever there's a serial predator, they always seems to show up at the neighbour's house and they say, tell me about Bob, the serial killer.

Stan Grant: The nicest guy you could ever meet. Yeah.

Mike King: Exactly.

Always brings me chicken soup, helps me when my battery’s dead and I need a jump, you know, so, yeah. And yet, uh, when he sneaks out and he's on the hunt, he is a horrid devil.

Stan Grant: I want to get to how policing has changed and technology and your role in leadership – but I'm fascinated by a couple of cases we might touch on really quickly. And that is, solving the murder of your great-great-grandmother who was a bit of a pioneer in the United States?

Mike King: That is so neat that you would even bring that up. And yes, I had heard the stories of my great-great-grandmother who was murdered on July 24th, 1891 in a little tiny area of Four Corners in the US, which is Utah and Arizona and Colorado. All my life I heard these stories from my grandfather.

And I remember I was about halfway through my law enforcement career and I thought, ‘holy smokes, I've been a police officer and investigator my whole life. Nobody's ever solved this murder. Let's start looking at it’. And so I spent about 10 years, every time I had a break, my wife and I would head to Southern Utah, and we'd dig around. And eventually we even went as far as finding the original report that was handwritten by the Sheriff in 1891, about her murder.

And over the course of that 10 years, we were able to piece together the case, use genealogy to really understand and come to know, again this victimology, who this woman was. And then finally we had this cataclysmic moment in my mind where we actually solved the murder and we packaged it all up in a nice little publication.

Stan Grant: I think one that would fascinate all of us – one of the great riddles of all time – the great mysteries is Tutankhamun. And you're involved in that investigation as to what happened there, was there foul play. How did he die? What did you find?

Mike King: Oh, that was such a fascinating case. I use that as a way to educate and teach police officers that you really can go back and investigate a cold case.

But the idea was we were invited by the Discovery Channel to come in and investigate that. And so we had the rare privilege of travelling throughout Egypt with Egyptologists, including Dr. Zahi Hawass who was the Supreme Director of antiquities at the time. And we looked at the case from an entirely criminal standpoint. We focused on four suspects and we whittled those suspects down to one. And the conclusion we indicated that we believed that he was murdered. It was a political assassination and we even theorised how that may have occurred.

It was a fascinating case. I'll tell you, Stan, one of the things that I'll never forget – I get shivers today when I think about it – is standing next to Tut's tomb by myself at two o'clock in the morning. No one around in the Valley of the Kings – in the bottom of this tomb of Tutankhamun's, which wasn't his tomb.

And he was just dumped there, which was part of the behaviour that we used to prove this homicide. But I just remember looking at this Pharaoh and thinking, holy cow, what is this dumb kid from Utah in the United States doing in Egypt, investigating this most famous Pharaoh of all time. It was just a splendid experience that I'll never forget.

Stan Grant: And if we looked at how crime has changed over time and the investigation of crime, one of the things that you talk about on your podcast is how people can move so much more freely and quickly. A crime committed in one state could be connected to a crime committed many States away, and how a perpetrator can move and how much more difficult that is to be able to track the movements of the perpetrator, but also to work across various jurisdictions.

Tell us about that.

Mike King: That is a real challenge and you and I are fortunate to be close in the same age, but when we were children the towns were close knit. We knew our neighbours. We sat out on the porch at night and chatted. We weren't inside with air-conditioning and video games. I mean, it was an entirely different world and the way in which we interacted with each other was entirely different. Well we fast forward now and all of a sudden you and I can jump on an airplane and be in a city a thousand miles away in an hour's time.

We could commit a crime there and be on another airplane in and out. But still law enforcement continues to look at these cases as if they're a single episode originating in one community, with someone from that community being responsible for it. And we have to change our thinking and that's why it became so important over the last 20 years that we've seen law enforcement agencies start to work harder at sharing information and collaborating on cases, because the offender today is so much more mobile than at any other time in our history.

Stan Grant: So how has technology impacted on that? I know for instance, improved processes around forensics was an enormous breakthrough and the use of DNA was an enormous breakthrough. But the ability to track people, mapping, being able to apply technology when you're dealing with potentially vast distances, different environments, different people, different cities.

Tell us about the application of technology as it tries to keep up with the rapid change and the speed of our lives.

Mike King: We're seeing changes not only on the forensic side, where we've moved way beyond just a single idea of capturing fingerprints to being able to look at body fluids and other kinds of things. Today, we can actually process those fluids in minutes and hours rather than having to wait months for kits on sexual assault or other things to come back. But, as we think of human movement and the ability to track today, with mobile devices and with watches on our wrists that track, with vehicles that have sensors in them, even our refrigerators now are getting sensors on them. All of this data becomes part of this thing that we call this, ‘Internet of Things’, or this collaboration of intelligence.

And what we've discovered is that everything, regardless of what it is, is tied to a dot on the map. It might be the location where a bullet casing falls on the ground after a gunshot or the place that that gun was purchased or the place where it was pawned after a robbery, all of those things become a dot on the map.

And if we can look at things geographically, we can see pictures that we have never had before.

Stan Grant: And I know looking at your podcast, there has been a missing persons case in particular that you've spoken about on a few different occasions and trying to track the movements of someone – and even a mobile phone of course these days – which are their own sort of tracking devices. Where a phone call is made. Where the next phone call was made. And when you look at that spread out on the map, it gives you a visual analysis, a visual indication of the scene itself doesn't it?

Mike King: Oh, yes. And what it does for those that are decision-makers is not only does it allow them to watch and provide some overwatch of protection that ‘hey, we have someone that didn't return from a search’, but those commanders and decision-makers can go in and say ‘we've looked through this area, but we forgot one really important part’.

And it may only be a 10-meter-wide section of ground, but if it's important and it was missed, we can now see that and go back and have that checked to get a second set of eyes on it. So it's amazing what we're able to do today with technology.

Disclaimer: Now it’s worth letting our listeners know, if you’re enjoying my chat with Mike you can also catch him on another podcast called Mapping Evil. It’s a little darker than this podcast but if you’re into true crime and learning more about the minds of predators, and those who bring them to justice then you’ll really enjoy Mapping Evil. I have to say I’ve listened to it and I’m completely hooked – if not just a little frightened.

Mapping Evil is available from the same place you’re listening to this podcast just search for Mapping Evil with Mike King.

Stan Grant: Now, you were no longer the rookie who was learning from his mentor, as you are the senior cop, you are one of the most celebrated police officers in the United States. So tell us about leadership and being able to bring people with you. And I would imagine I mean, my own profession – journalism is certainly guilty of this, and I've been guilty of this – of relying on the tried and tested ways of doing things. Things that may well have worked and you've built a career on, but how do you adapt? How do you change and what is, what do you bring as a leader to that change?

Mike King: You know, I think one thing that that happens in the course of our life is we make enough mistakes that we also start to learn to slow down a little in the decision-making that we're going through.

There are times when you have to make a decision quickly, but in most cases, being able to bring people around you and collaborate and get ideas. Ideas from young people who look at things entirely different than an officer that has 20 or 30 or 40 years of experience. It's necessary that we bring those two sides together and find out how to solve problems. More wisdom than maybe you have in your youth.

Stan Grant: I love that idea of slowing down and being more wise. I want to take your leadership, your expertise, your experience, and apply it to a hypothetical. We like to do this on the podcast. We like to take you, maybe out of your comfort zone a little into something else. We're going to bring you to Australia. And I know you've been to Australia before, and take you to a cold case, a famous cold case.

Now there is a lonely outback stretch of road. 11 people have disappeared, and these mysteries remain unsolved. They're hitchhikers sometimes, sometimes young schoolgirls, and recently there was renewed attention around a particularly high-profile case. A missing person, ultimately put down to a suicide, but the body was never found. And the family and community members believe that there is someone lurking out there, a killer. New physical evidence is uncovered that challenges this idea of a suicide theory. You are brought into the case.

Mike King, you're brought across from the United States. You've got this great eye. You've solved the killing of King Tut, and they're bringing you here to be able to apply your experience to this. Where do you start?

Mike King: Well, I think you have to start at the foundation first. You've got to go back to ground zero and start learning. Number one, learn who the victim is. And again, this idea of victimology is so important in these kinds of investigations. Sometimes that means really digging into things that make people uncomfortable, family members or others, but if there's truly a desire on both sides of the fence to solve a crime you've got to get that victimology down.

You have to understand what's happened from ground zero moving forward. And my experience has been that law enforcement may make, or have opinions on cases, but they always remain open to new evidence – especially we've learned, evidence that comes through forensics for instance. We're getting evidence today that we've never had before. So we need to go back and re-examine the case from a forensic standpoint, we need to look at the other forms of evidence that are a part of that case.

Some of those might be eyewitness accounts. What did they really remember? What do new witnesses that didn't have the courage 20 years ago, or whenever this case was until today, maybe there are people who have gained the courage in that 10 years, or that span of time to step up now and say ‘I saw this’ or ‘I heard this from someone’.

New information can be collected. And so we look at those forms of evidence, which might be eyewitness accounts. It might be circumstantial things, like this assumption that it was a suicide. Well, if it was a decision made only on circumstantial evidence then is that really a strong stance to have? Because in policing, what we want to do is make decisions based on multiple forms of evidence, that we have circumstantial, but we maybe have physical evidence to support a theory, that we have eyewitness accounts, and that we have behaviours to look at.

And you mentioned one of my favourite sleuths of all time at the very beginning Stan, you mentioned Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. And if you remember his famous statement, “It's a capital mistake to theorise before you have all the facts, for insensibly, you spend all of your time bending and twisting the facts to meet your theory, rather than gathering facts and then creating a theory”.

Stan Grant: So I want to take you to one fact that indeed may have shaped the nature of the investigation. This is a small town. It's a town that has its own history of racial issues. And the girl who went missing here is an Indigenous Australian. Someone who lived in an Indigenous community. It's a community and a town that over time had been segregated, and there were sometimes even hostile relations with the police.

Now there are real questions being asked here, that perhaps the police didn't apply themselves in the way that they may have. How do you approach that and what may have gone wrong here in terms of the victimology, as you said, identifying the category of risk and how you apply an investigation to that?

Mike King: This makes me so excited Stan, because it opens an opportunity of healing in some degrees too, because, indigenous communities, we see this happening, we have our own indigenous communities in the States. I've travelled into your communities, especially around Uluru and visited with the people there. There is without question, historical evidence that supports that there are biases and prejudices that exist in every level of government and every personality.

We hate to think about that, but there are stories that satisfy that. With this new challenge that you have thrown out where you have this opportunity to go in, it is so exciting to be able to go in and start to communicate with every community and let them know that there's equalization when it comes to crime and investigations. That if there were mistakes made that they need to be rectified and those things need to be researched and figured out.

Sometimes you can't change opinions about whether someone feels a bias feeling towards someone else, but by being transparent, you compel people to play on the same level playing field. These things shouldn't be kept hidden from people or secrets shouldn't be kept.

Stan Grant: Now Mike, you do some investigation into this girl's background and you find that yes, she'd had a tough time growing up.

She had been in a relationship. She had three young children. The relationship had broken down. The father had disappeared. But she had committed herself to being a good mother, raising children. She had a permanent job that she'd held for several years, working in the local supermarket. And she had risen to a level of responsibility.

She was a shop manager. She was responsible for other staff. When you spoke to her bosses, they say that she was punctual. You can set the clock by this girl. She was friendly. She was engaging. She was someone that could be relied upon. And yet she disappeared. You go back to the police and you say, listen, this girl was not someone who would walk away.

And they say to you, Mike, you're an outsider. You don't know these people. They always walk off. You don't know what you're talking about. The case is solved. She killed herself. What are you doing? What do you say then to that?

Mike King: I think number one, I don't know that I say anything at that point because I still am gathering those facts.

I need to know what those original reports say, what those original victim or witnesses say. But then I need to level set and then balance that against the new information that's come forward. It is really tragic if anyone, whether they are citizens or sworn police officers, make decisions of whether someone deserves something based on what their background was or their life choices.

Even if this person, everything they said was true about them, Stan, they didn't choose to get murdered or to be victimised. They may have made choices that placed them into positions where their risk level increased. But they didn't walk out saying I want to be victimised and hurt or killed. And we have to treat them as victims of crime with the same impunity that we would anyone else. They deserve that.

And so it requires sometimes standing alone to say, no, we're going to gather all the facts we're going to re-examine and we're going to make another decision.

Stan Grant: What happens though Mike, and you're a fresh pair of eyes. That's why you've been brought in. You've been brought in because you're outside of that culture and you're a leader, but you run up against here some police who won't work with you. Who start to hide information from you, who are stonewalling, who are thinking, well if we just run down the clock on this, he'll go back to the States and we can leave this case where it lies.

How do you deal with that as a leader? At what point do you assert leadership to be able to get people to work with you when potentially you're facing obstruction, if not even some hostility.

Mike King: Yeah, I think you have to open every channel of communication Stan. That might be the public. It might be people inside of the organisation to provide information from an anonymous standpoint. You have to accept and understand that you might get stonewalled by somebody and that you might even get blocked by somebody – but this is where it gets lonely in leadership.

You either have to decide you have the integrity to keep fighting, or you have to give in, and that's a really lonely place, but when you're an employee that's living on a paycheck from month-to-month and paying your bills versus someone that has now got a retirement and coming in and it's under a consulting fee.

Those two are two different worlds, because you have a mission to accomplish. You're not part of that system. You're coming in to do something. And yet along the way, you have to build a team and have the support and have people behind you as you do this. So it creates a real challenge and frankly, leadership is lonely.

And you find even when you're promoted through the ranks, that as soon as you're promoted, people who were your friend yesterday, are now the ones that are jabbing behind your back and saying what a jerk you are.

Stan Grant: As a leader, when do you get tough?

Mike King: I think you get tough immediately when you realise that you have an obligation to the men and women that you serve that are under your command, to the community that you serve.

There's a point where your integrity has to step up and say, what is the right thing to do? But you've got to have the integrity to step forward, even when you're standing alone.

Stan Grant: Now you've applied the use of technology you've gone back and you’ve said, look, we can now discover things about this girl's disappearance. We can open up an investigation to the disappearance of others on this lonely stretch of highway. We can now map where people have been because we have the capacity to do that. You go back and you'd look at the mobile phone records and you check the phone records of the people in the town.

And you find that, here was the person who was everybody's friend. And now you've found that in each of these cases, his phone record matched the disappearance and the location of some of these other victims. You've broken this, but you also know what this is potentially going to do to the town.

Potentially going to do to the police officers who did not properly investigate it, and potentially to those people in the indigenous community who are going to say, well you neglected to do this. They neglected to do this because they didn't care about our lives. You've solved it. But now you have to bring this to a conclusion with the healing that you spoke about before.

How do you do that?

Mike King: I think a couple of things. Number one, I've had in my career many opportunities when I was at the Attorney General's office to take over cases very similar to this where you knew you were going to offend your peers, maybe even people that you've worked with on other cases, but right is right. And you need to move forward with that in mind.

Also it needs to be done humbly, and talking to people and saying, here's the evidence that's coming forward, and here's what we're going to do, usually we'll help you bring people along. Even those who may have made decisions based on theory before they ever had facts. And you can still make many of these people part of the win, and part of the reason why this was successful. It's a hard jump for some people to say ‘I've changed my mind’. But it is such an important part in all of our makeups to be able to do that – to say I've been influenced by more information and more evidence.

You need to be transparent with a community. It's okay to say there were mistakes made, or we missed some things along the way. That can be said in a way that doesn't demean those who stood before you and made those decisions. Sometimes it's more about the delivery than actually what's being delivered.

Stan Grant: Mike, we've learned so much about your own personal style, that you are someone who is collaborative and inclusive. I think I can gather from the way that you've answered a lot of these questions that you have faith in human nature, and you like to put trust and to build trust with people, but you're also open to calling things out and you're certainly open to new ideas. I want to ask about how you have taken that leadership and applied that in other aspects of your life?

And, how you've been able to speak to other people in other walks of life, and establish these foundations of leadership that are applicable, that you've learned from your years of policing, that are applicable elsewhere.

Mike King: First and foremost, and, and I have to give credit back a Deputy Attorney General and an Attorney General I remember serving under. I remember one particular occasion where I wanted to fire an employee who was involved in some things that were just outrageous in my mind.

And I remember them teaching me, don't make this personal, make it about behaviours. Let's not talk and make things an attack on an individual. Let's talk about the behaviours. And oftentimes I found in my own experiences, rather than me sitting down with someone and saying you made this mistake and that mistake. I found I could sit down with them and say, tell me how you think things are going in this regard.

People generally throw themselves under the bus much more quickly than I could ever bring something to their attention. Then you have a place to work from that's constructive and, and you're able to move forward in a way that seems to make better sense. I think treating people with dignity, again, it goes back to this idea that we discuss behaviours, not that we attack personalities or who people are. And when we do that, whether they're victims of crime or family members of crime or perpetrators, we get things done more quickly and people are willing to have you stand alongside them and solve a problem.

Stan Grant: And technology as well, I mean your willingness to be open to new ways of doing things, and you've been involved with the mapping technology giant of course, Esri as well, you've been involved in taking some of that technology and its application and being able to use that in other ways. We know for instance, that in terms of being able to work with big events – where you have enormous numbers of people – they're logistically complex events.

You're talking about big sporting events for instance, or major political events. How do you take that technology in your experience and having worked in that, and be able to apply that to being, able to provide security around major events that involve large numbers of people and are logistically complex?

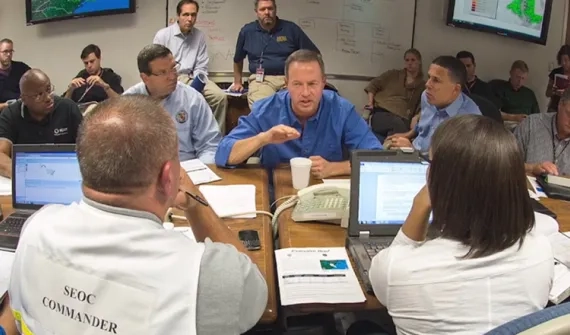

Mike King: You know I had one experience that I often reflect on which was a huge event. I ended up with 27,000 individual workers that we were monitoring over a seven- or eight-week period of time as we managed this event. And in that, we had to manage locations that they were securing and taking care of.

We had to manage things as simple as restrooms and whether they were being over overused and make sure that they were being cleaned on a regular basis. We were managing areas for protestors to stand and do their thing and exercise their right. And by being able to use geography to first and foremost, understand the entire theatre was one of the greatest blessings of all.

We used, of course, Esri technology to bring all of this together and know where everyone was at every given moment, and where they needed to move when shift changes occurred, and when other kinds of things happened. Where we were going to bring medical services in if we needed to have someone come in to bring an ambulance and take someone away. Where we were going to have arrests that occurred and move people off site.

But then we started tracking all of the social media and of course we're able to do that through a number of means in the States. We could then see what was socialised, what people were saying. So we got a heartbeat of people that were complaining about standing in line too long, or this person spoke meanly to me and understand from that perspective what was happening. But then to manage all of that human movement and review it at the end of the day, and see how things worked, helped us to prepare for the next day and fix the gaps or the shortcomings that we had.

Technology has moved us forward in a way that I've never seen in my career and that law enforcement or any agency or organisation could take advantage of, so that they better manage people, resources, and the eventual customer that they serve.

Stan Grant: And of course, if something was to go awry and there was a need for an investigation, you've already got a baseline of information don't you? By being able to set up those protocols and being able to apply that technology to the planning of such events. If there was in the worst-case scenario – a bomb went off, people were killed – there is the potential there to go immediately to work and apply all of those principles that we've talked about today.

Mike King: Absolutely. And those commanders that are in the field, or they're sitting in a command centre, are getting real-time responses from people, either in the field or from other kinds of sensor data so that they can make decisions rather than kind of making a gut decision.

Stan Grant: I want to just finish off on where we started, and that is the idea of profiling and how that can be applied even outside of policing and apply it in other walks of life. Whether you're employing someone, there are so many areas where we make judgements, or we make decisions based on what we can glean about a particular individual.

There are risks in that too aren't there in the assumptions that can come and we saw without our hypothetical. The assumptions that were made on the basis of someone belonging to a particular racial group or a particular socioeconomic class. How does that go wrong as well as right in terms of profiling?

Mike King: Well, I think we all are victims of our own personal biases for one thing. We have to be so cautious that we don't make assumptions. It's said that he who is good with a hammer, thinks everything is a nail. Just because one process worked today on a missing person case, doesn't mean that same strategy is going to work tomorrow because the victim is different.

The people surrounding the victim are different. The environment may be different. So we have to be flexible enough to be able to move the pieces around as needed. But fundamentally things remain the same. And we have to be also aware of our own personal biases and how they might impact the way we do things.

We see this with young police officers that show up the first time on a family fight or the victimisation of a child in a child abuse case. And immediately they're referring back in their psyche, I've got a three-year-old kid. I'd never treat this three-year-old the way this person has treated the three-year-old, and we allow those things to influence our decision-making.

So, we have to recognise that those things can really impact us along the way.

Stan Grant: And just a final thought from you Mike, as well about those people, and you've come across this no doubt in policing. We talked a little bit about it earlier about my own profession as well of journalism, where there is a resistance to change. For people who are not adapting or embracing technology as a leader, how do you bring them with you?

Mike King: The only thing that I've found that is successful is continued mentorship. Sometimes the best way you bring people along is you encourage them that it's time to retire and find something they can be happy at.

Stan Grant: That's a very nice way of saying it.

Mike King: Yeah. I mean, I wonder Stan sometimes if we're afraid to say, let me help you find a job where you can be happy because you just don't seem to be successful here.

And that's the role of a leader. You either build people, or let's help them find a place where they can be good at something. Because everybody wants to be good at something. But along the way, if we can introduce people to things in a way that helps them become better, that gives them a few pats on the back, and why we're afraid to compliment and pat our people on the back sometimes is beyond my thinking, because I have always worked harder for the boss that believed in me and I never wanted to let them down because I knew they thought I could do more than I really was capable of. And we need to somehow as leaders help our people understand that we are in full agreement that they are capable of great things.

Stan Grant: It's been an absolute pleasure talking to you today Mike King. Thank you so much for giving us your time. You've been very generous.

Mike King: Oh no, it has been my honour, thank you.

Stan Grant: As usual, if you'd like to learn more about Mike or get your hands on a free trial of the crime analytics software he uses, visit directionspodcast.com.au. Mike also has that fascinating podcast series Mapping Evil where he talks about how he cracked some of the world's most heinous cases and explores how understanding the geography of crimes, predators and victims can shed new light on unsolved cases. It's a must listen, and you can stream it now at mappingevil.com.au.

On the next episode of Directions, Chief Kim Zagaris has been involved in every catastrophic emergency in California over a distinguished 40-year career. Under his leadership he’s seen technological innovation completely change the way agencies respond to emergencies.

Chief Kim Zagaris: I’ve been through a lot of disasters not only in California but around the country such as Oklahoma City in 1995 and the Murrah building bombing and the support of nine 11 and our own floods and own emergencies. But I will tell you that to me, at the end of the day, what's really made things come together is just watching the business that I'm in evolve over and over and over.

We constantly, much like the news business have to, remake how we're doing it, how we're meeting those challenges. Coming up with new technologies, new ways of adjusting to meet the needs for the next go around that's what's been really neat about it.

Stan Grant: That’s the next episode on Directions. This is a Boustead Geospatial Technology Production supported by Esri Australia. This episode was narrated by Stan Grant and Mike King. Sound engineered by Nearly Media and Deadset Studios, with editing support from Kim Douglas and Sydney Podcast Studios. Artwork by Superscript and our Executive Producers are Alicia Kouparitsas and Raquel Jackson.

If you like our show please give us a five-star rating, leave a review and be sure to tell your friends. Follow us on Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also download a free trial of Esri software, check out our show notes and access other resources at directionspodcast.com.au.

The views and opinions expressed in this podcast are solely those of the participants and do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of Esri Australia, its subsidiaries or partners. Hypothetical scenarios presented as part of this episode, are purely fictional. And while they may draw on current issues, they do not depict the actions, values, or beliefs of any specific individual and/or organisation.

And finally, this production would not be possible without the support of Esri Australia.

VIEW TRANSCRIPT

VIEW TRANSCRIPT