As part of their continual fight against drugs, governments and public safety officials are increasingly turning to Geographic Information Systems (GIS) technology to give true visibility to the severity of the problem.

Fuelled by the recent spate of deaths of young adults, who died from drug overdoses after attending music festivals, the fiery debate about pill testing has renewed advocates’ calls for drug policy reform in Australia.

Even if pill testing is introduced though, it’s unlikely to provide a silver bullet solution. Drug use at music festivals is just one aspect of Australia’s growing drug problem. According to the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission's latest analysis of wastewater, Australians spent about $9.3 billion in 2018 on cocaine, meth, MDMA and heroin.

Many factors come into play when trying to address a complex issue like this – not the least of which is identifying the true scope of drug use, understanding drug user motivations and demographics, and rolling out public education campaigns. Afterall, if something cannot be measured it cannot be managed.

US law enforcement expert Mike King outlines how authorities are using location intelligence to report drug activity, educate the community, promote treatment options and understand the effectiveness of response activities.

Q. How can GIS technology help in providing a picture of the drug problem at a local, operational level?

At its most basic level, everything related to say, a single drug overdose can be tied back to a specific location – for example, where the overdose occurred, which hospital the patient was taken to and where they lived.

Mapping technology allows such location-based data to be entered into a system which can then provide an aggregated view in overdose and death maps, both in real-time and over a period of time.

When used in real-time for example, these maps can be used to highlight specific clusters of overdoses as they are reported – say in the event of a music festival, where a number of people are admitted to hospital in a short period of time. For local law enforcement authorities, this data could help to inform where to send first responders and how many to send. It could also help to flag that a contaminated batch of drugs is doing the rounds in a particular area.

Over the longer term, this data can be visualised in a way that can help to identify patterns and trends in drug use, which can help to educate the public and inform policy reform.

The City of Tempe, Arizona, is just one example of a local authority using GIS-powered dashboards to monitor opioid abuse. Its publicly-available dashboards show the number and demographics of each case, and the approximate location. It even goes into details such as veteran status and looks at vulnerable populations like children and which age groups are being affected. It gives the authorities the ability to see in real time where people in different age groups are overdosing. A detailed story map is available here.

Q. What about scoping the problem at a national level? How can mapping technology help government agencies communicate the problem?

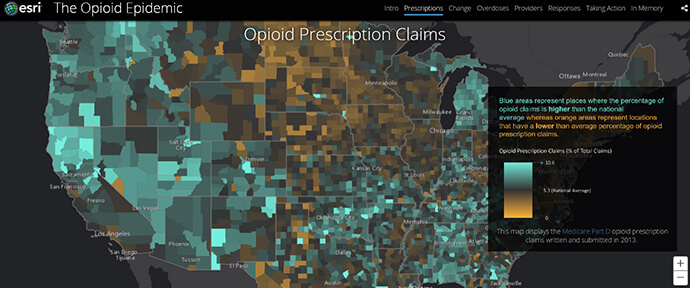

Today’s sophisticated mapping technology also allows story maps to be created relatively easily and quickly. In this instance, The National Association of Counties worked with Esri to create a story map to show the number of overdoses nationwide. As an overview of the national problem, the map also tracks opioid providers and filled prescriptions.

With 78 Americans dying every day from an opioid overdose, drug-related deaths in the United States have hit an all-time high. The number of prescription opioids sold in the US and the number of prescription opioid deaths have both quadrupled since 1999. Since then, over 165,000 people have died from prescription opioid overdoses.

A major step in addressing this issue is improving the way opioids are prescribed. Better clinical practice guidelines will lead to safer, more effective pain treatment as well as a decrease in misuse, abuse, and overdose.

Providing a geographic view of opioid prescriptions sold across the country, clarifies how counties and post codes compare to each other, their state, and the nation as a whole. Once we understand this broad picture, we can start to look at how to best educate local communities.

Q. It sounds like there’s a lot being done in this space in terms of visualising the problem. Could law enforcement agencies use mapping technology to track the use of drugs back to dealers and drug labs, and ultimately help to stop the supply of drugs?

Quite possibly. It’s interesting that the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission's study analyses wastewater to identify drug usage around the country.

I’m aware of a fascinating study in the US using Esri’s technology, which reverse engineers that scenario and measures opioid chemicals that are disposed into the sewer system to backtrack to where the chemicals are originating. This can all be visualised on a map.

It’s still early days for the study, but the implications for tracing chemicals back to specific locations – whether they happen to be drug users or drug labs, opens up substantial opportunities for law enforcement agencies who embrace the mapping technology helping them make sense of all this data.

If you’d like more information on how GIS can support your operations, call 1800 870 750 or submit an enquiry.