The accuracy of mapping data, and the way it's used, can have a fundamentally positive - or negative - impact on the search for a killer.

In early January, a coroner reported that a missing Australian's body could have been found 18 months earlier had searchers not relied on incorrect Google Maps data. The coroner recommended that police be ordered to conduct future searches by using high-quality GPS and mapping data and improve their communications with search volunteers.

There’s no doubt that locating a missing person or dead body is like searching for the elusive needle in a haystack. However, law enforcement agencies that use advanced mapping technology as a core part of their operations can conduct searches more efficiently and accurately – improving their efforts to solve crimes faster.

In part two of this three-part blog series, US law enforcement expert Mike King, outlines how investigators can use Geographic Information System (GIS) technology to combine location-based data, public information and suspect profiling data, to help catch killers.

Q. In what sort of ways can law enforcement agencies use GIS technology to assist criminal investigations?

In most crimes, various types of evidence are collected. There’s physical location evidence, such as the location where victims come into contact with the perpetrator(s), the location where the criminal event(s) occur and in some cases, the disposal site of the victim after the event. Then, add to that, the traditional forms of evidence such as eye witness accounts, circumstantial or forensic events. For each of these, location is a factor and can help in understanding important behavioural aspects of the crime.

GIS technology adds additional insight into these investigative clues through visual representation on a map, building a multi-dimensional view of the crime.

In harnessing the power of citizen engagement, agencies around the world that have given the public the opportunity to view appropriate information on missing persons, unidentified and recovered bodies and ongoing homicide investigations, have gained valuable tips that may not have otherwise surfaced. These modes of information sharing make it possible for investigators to receive vital details anonymously, providing a valuable source of actionable data.

Web surfers might say, ‘Hey, I think you should check over here’, or ‘I remember when I was 15 and those murders were occurring, and someone I went to highschool with said something really weird.’ Tips like these are extremely valuable and are needed by today’s law enforcers who struggle with personnel, budgeting and time constraints.

By asking the public for information in a format that’s both easy for them to provide and for us to access, we can geographically analyse the data and share it with those ‘who need to know’.

Q. Can you provide any specific examples of where GIS technology was used effectively to collect and analyse information from the public?

We had a serial killer case in San Francisco where investigators were planning to canvass the neighbourhood. They were physically going to go to every house and ask three questions: Were you living here 20 years ago when the murders were occurring? Was there anything that you remember, and would you be willing to talk to police? The plan was then to call in the dispatch and report the response from every house.

Hearing about this, the GIS Manager created a simple collector application that could be loaded on any mobile device. In less than two hours, dozens of investigators were equipped to use the app on their mobile devices – and they were collecting responses in real time. Commanders in the operations centre watched the collection effort in real-time, making data-driven decisions that were based on current information. The investigation became a far more efficient search, eliminating the need for handwritten notes, spreadsheets or time-consuming interaction with dispatchers.

Q. The recent Australian case highlights the need for more rigorous use of high-quality GPS and mapping data. Can you share any examples of how GIS is being used to search potential crime scenes?

The Alabama Law Enforcement Agency (ALEA) used high-quality GPS and mapping data when it conducted an exhaustive search of a 300-acre property in rural Alabama, as part of investigations into a 20-year old cold case.

Using digital maps created from more than 2,200 photographs captured by drones, the investigating team and 200-plus volunteers were able to canvass the entire property in just four days.

By symbolically casting a ‘geographic net’ over an area of operations, small geographic zones can be managed and analysed. As a more efficient process supported by GIS technology, assignments can be made, personnel can be tracked, and information can be collected in a comprehensive and efficient manner.

Through geographic analysis, we can achieve much better outcomes: we can truly evaluate the effectiveness of searching an area as well as visualise it for operational commanders and the public when appropriate.

These are the kinds of problems that GIS can solve, and which sadly, most law enforcement agencies are not taking advantage of.

Q. What about cases involving serial killers? How can geospatial data and applications assist in these longer and more complex investigations?

Years ago, a serial killer by the name of Robert Ben Rhoades preyed on hitchhikers and truck stop sex workers. Known as The Truck Stop Killer, Rhoades was convicted for three murders, and the charges for another two were dropped before the cases got to court. He’s also suspected of torturing, raping, and killing more than 50 women between 1975 and 1990, based on data about his truck routes and women who went missing during those years and who met the profile of his preferred victims. In all, profilers at the FBI who worked the case theorise that Rhoades is potentially responsible for more than 300 missing persons cases.

In that investigation, GIS could have been used to explore where the victims went missing, and the locations of the truck stops that Rhoades visited. Network analysis may have helped determine how far he could travel between one truck stop and another, and still be able to reach the area where another victim disappeared in the same timeframe.

With GIS, we can go from possibilities to probabilities much quicker.

Q. You’ve mentioned that almost everything related to a crime can be tied back to a location and visualised on a map. How does criminal profiling fit into this picture?

We do a lot of this sort of work at the Cold Case Foundation. This organisation is made up of retired and currently working profilers, medical examiners, forensic scientists and some of Esri’s geographic scientists.

When there is a serial event, we try to categorise and visualise data in three separate buckets:

- The initial contact sites – where people encounter each other

- The location where the crime occurs

- The disposal site where the bodies are dumped

All of these elements are obviously geographic, but if we look beyond that, and start looking at personality types and the emotional focuses of the offender, it all becomes geographic too.

For example, if it’s an offender who’s focused on children, we start looking at geographic locations where children are going to be.

If we determine through personality analysis that the offender is someone who’s selecting a victim they know versus someone they don’t, we can then start to look at why they’re choosing the location of where they come into contact with that victim, the significance of the site and its relationship to what brought them together. It might just be the place they bought the rubber gloves or rope they used – but even that can have a geographic significance.

Geography becomes incredibly important because the perpetrator picks that location for a reason. It might be convenience, it might be part of a much bigger scheme they have in play – it’s all important, right down to the very moment of gunshot being fired and the location the casing falls. That is a geographic location. The shop where the gun is pawned becomes a geographic location. The place where the offender says they were during the crime spree – all of it is based on geographic location.

And that’s what the Cold Case Foundation looks at – suspectology and victimology as a whole. The Foundation then tries to determine, based on all those other factors, who might be responsible. This information is provided to local governments together with strategies for interviewing the offenders, or identifying what kind of offender they’re looking for.

Q. You’ve outlined how GIS can help both individual and serial cases. How can national (or international) organisations make use of geospatial data and applications to get a broader perspective of crime?

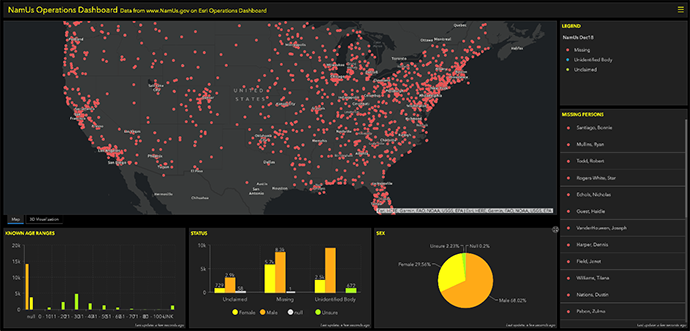

NamUS, the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, is an information clearing house that provides resources to law enforcement, medical examiners, coroners, allied forensic professionals, and family members of missing persons.

Organisations like NamUS, the FBI’s Violent Criminal Apprehension Program and like-minded organisations around the world are relying on GIS and maps to show information such as the location of missing, unidentified and claimed bodies, and the demographics of those victims.

When you can visualise huge volumes of data from across the country in such an easy way, patterns and trends start to emerge. This ‘big picture view’ also demonstrates the true scope of the problem – in this case, the number of missing persons and the impact on law enforcement agencies of managing thousands of cold cases. While it may seem grim, this picture can also help to justify government expenditure and the allocation of resources to those areas they’re most needed.

This is the second interview of a three-part series with geospatial law enforcement expert, Mike King. In the first interview, King discusses how law enforcement agencies are increasingly turning to GIS technology to manage and prevent drug-related deaths. In the third, he’ll discuss the importance of 3D data for emergency services.

If you’d like more information on how GIS can support your operations, call 1800 870 750 or submit an enquiry.