The team tasked with designing the first underground railway under the heart of Australia’s fastest-growing city knew it would be a delicate task, fraught with infrastructural peril. Tunnelling several stories under Brisbane’s teeming metropolis, constructing expansive subterranean stations—what could go wrong?

As of January 2023, the scheduled project completion of Cross River Rail (CRR) is less than two years away and it’s clear they made strong choices. But at the outset, nobody knew that the effort would involve an ingenious application of a geographic information system (GIS), creating a detailed and up-to-date 3D model of the project and the Queensland capital city above it, and an immersive digital twin that brings the project to life.

A rapidly growing Queensland

The Queensland government conceived the Cross River Rail project as a way to alleviate population pressures. By 2036, the South East Queensland metro area is projected to add another 1.5 million residents (a number that by itself would make it Australia’s fifth-largest city), pushing the region’s total population to nearly 5 million.

Current rail infrastructure is insufficient to handle the necessary increase in CBD-bound train traffic. Cross River Rail will add 6 kilometres of twin tunnels under the river and four new underground stations.

A bigger, better model

Soon after the project was announced, the Cross River Rail Delivery Authority, the overseeing agency created by the Queensland government, sought advice from colleagues on the other side of the world. The Crossrail project in London, launched in 2009, has similar aims, creating new tunnels and ten new underground stations throughout Central London.

Crossrail involves construction beneath a metro area even denser than Brisbane’s, with extremely narrow margins to avoid damaging existing underground infrastructure. “They’re like our big brother that we idolise,” said Russell Vine, Cross River’s chief innovation officer.

By the time Cross River’s plans were beginning, Crossrail had been under construction for almost seven years. The Cross River team contacted their British counterparts and asked what, if anything, they would do differently if they could start over.

“They basically said, ‘we would have built a bigger, better 3D digital model sooner,’” Vine said. The big brother then offered three steps for how to build the perfect GIS-driven digital twin:

- Create a common data environment

- Stipulate that all contractors use the same standards in their 3D architectural models, so they can all combine into a single model

- Make the model immersive

An expansive mission

For starters, London's Crossrail recommended that Cross River create a common data environment for all work. Any project-related dataset, no matter what the format—GIS, building information modelling (BIM), volumetric, photogrammetry (a three-dimensional coordinate measuring technique that uses photographs), everything—should be in a central repository.

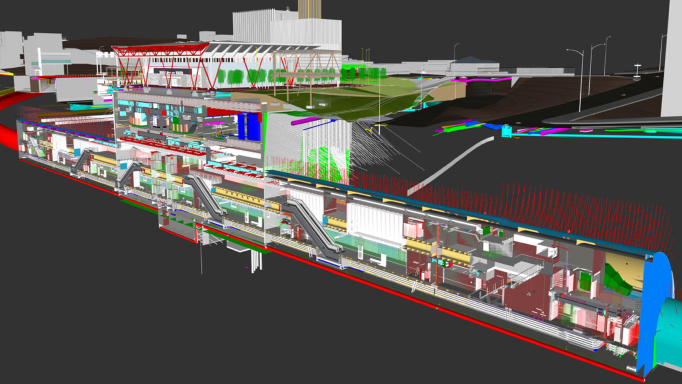

This was useful advice. In recent years, GIS technology has become adept at integrating BIM models and other project-related data formats into a GIS environment. BIM models are 3D architectural models. They describe and depict the actual things being built or dug, while GIS adds contextual awareness.

Rather than just consider the BIM models as inert objects floating in space, people involved in a project can visualise what’s around them. In GIS they can see how each structure fits into the infrastructure above ground (such as paths, roads, and light poles), underground (the pipes and lines that connect utility services) and to the natural world (landscaping, groundwater, and even wildlife and biodiversity considerations).

More than a railway – a city regenerated

The advice from the UK project also helped Cross River handle a broad mandate. When Queensland’s government created the Cross River Rail Delivery Authority, it required the agency to be responsible not just for the railway itself, but also for planning and assessing the project’s economic impact. There was a good reason to include this mandate in the agency’s charter. Although Cross River’s aim anticipates future developments in the region, its location means Cross River will also influence those developments.

“Cross River Rail is going right under the CBD, so the area around the stations is already prime land where the city will grow next,” Vine said.

Everything in federation

Crossrail’s second piece of advice related to BIM data coming from the project’s many contractors and subcontractors. Create a “federated” BIM model, the Brits advised. That meant combining the disparate BIM information into a single BIM file that depicts everything. For that to happen, Cross River needed to ensure that every contracting entity was using exactly the same data formats, standards, and protocols.

Rail games

Crossrail’s third recommendation is “the party piece, the one everybody loves,” Vine said, because it’s about making the model immersive. “They told us they should’ve put all their data into a game engine and turned it into virtual reality.”

The Australian team did just that, using Unreal Engine, a 3D gaming tool, to tie it all together, so anyone sitting anywhere could be transported inside the place they were set to build.

“So we have a federated BIM model of all the stations and all the tunnels, and GIS land mapping in 3D,” Vine said. “But then we put it all into Unreal, crank the magic gaming engine handle, and it gives us back a single virtual reality.”

The digital twin expands to capture all of Brisbane

Cross River’s commitment to the common data environment (step one of the three-point plan recommended by the Brits) signalled a shift in the usual relationship between GIS and BIM on this kind of large infrastructure project. In the past, GIS for sure would have served as a crucial support player, a context-adding host for the 3D architectural BIM renderings. But given the mandate to document economic development around the train stations, Cross River elevated the importance of GIS. To depict those above-ground areas, Cross River would require skilful 3D maps, including data gathered by Lidar sensors to capture engineering-grade measurements.

That, in turn, led to another requirement. The above-ground data would also require context.

If the goal was to understand how the stations would affect economic development in the CBD, it didn’t make sense to map just the area around them. You needed a map of the entire CBD. And everything would need to be layered perfectly, so that anything underground (stations, tracks, tunnels, cables, and pipes) lined up in every respect with what was above it.

The result is a 3D land layer that shows lots, utilities, and other pertinent visual information.

A twin without end

The Cross River Rail digital twin is a continuous work in progress. As designs are finalised and construction proceeds, a staircase or tunnel that existed as a single item in a contractor’s initial BIM submission becomes one with thousands of individual components in the federated BIM model.

Beyond just the Cross River project, there’s no reason the digital twin can’t continue to grow in perpetuity, evolving with Brisbane itself.

View the “Mega Timelapse” video below to see how the project progressed in 2022.

Read more about how Esri technology and our strategy teams work with clients locally and internationally to modernise transport systems.