Dr Kathryn Sullivan tackles the world’s biggest challenges with a little innovation

Dr Kathryn Sullivan's innate curiosity and love of exploration has led her to outer space, to ocean floors, and to leadership roles solving complex issues like climate change, poverty, inequality, and political unrest.

As a specialist geologist, Dr Sullivan was recruited by NASA to become the first American woman to walk in space in 1984. She was also the first woman to dive to one of the earth’s deepest ocean floors. Dr Sullivan led the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, one of the world’s most important agencies. There she worked to track and map how the earth is evolving and how our climate is changing.

Now she’s coupling her sense of exploration with spatial technology to help better understand how interdependent life on this planet really is. Named by the BBC as one of 'the most influential women of 2020', Dr Sullivan leads so generations may follow.

Never miss an episode of Directions with Stan Grant – subscribe now.

Never miss an episode of Directions with Stan Grant – subscribe now.

- Click to view the episode transcript

Kathryn Sullivan: The space age is the first time in human history that you really can say, we can take a snapshot of the entire planet, the distribution of moisture in the entire global atmosphere essentially, now. Temperature on the ocean’s surface everywhere on the planet, essentially now. That's thanks to satellites. And that ability to get that essentially instantaneous snapshot, this is the state of the planet right now, those are the data that let you run computer models that allow you to forecast or predict ahead.

Stan Grant: It's not often, you get to talk to someone who's been to the greatest heights and the depths and I'm not talking metaphorically here or emotionally, but to travel to space and the deepest parts of our ocean. As a specialist geologist, Dr Kathryn Sullivan was recruited by NASA and immediately began smashing ceilings.

The first American woman to walk in space in 1984 and the first woman to dive to one of the earth's deepest ocean floors.

I'm Stan Grant and on Directions, Dr Kathryn Sullivan tells you how she's led some of the world's most important agencies to track and map how the earth is changing, something we so desperately need in the face of climate change.

Support for this episode comes from the country's leading mapping technology and services provider Esri Australia. To learn more about how is Esri tech is supporting the world's most progressive leaders, visit esriaustralia.com.au/trailblaze.

When Dr Kathryn Sullivan was a child, she always chose the toys that moved, the ones with leavers or pulleys, the toys you had to figure out. Curiosity, exploration, the constant pursuit of knowledge. These things are so vital as we face those complex issues like climate change, poverty, inequality, and political unrest.

Dr Sullivan's been a NASA astronaut, one of the first women to walk in space and she's mapped some of the deepest, darkest, most inaccessible parts of our ocean. And now she's coupling her sense of exploration with Geographic Information System technology to help us understand how interdependent all life on this planet really is.

Welcome Dr Sullivan.

Kathryn Sullivan: Pleasure to be with you, Stan.

Stan Grant: You know, you have this thing when you're young and you know, you're often asked in class, what do you want to be when you get older? And people say an astronaut, few people actually get to do it, and you actually did. Do you pinch yourself sometimes and go, did this really happen?

Kathryn Sullivan: Well, you know I'm one of the odd children that didn't say that, the title per se is not what grabbed me. But around the time of the early mercury astronauts in the United States, there was also a big push towards the oceans. And so for three or four years I think of my early childhood age 10 thereabouts, I would see in every weekly magazine, monthly magazine, TV broadcasts, these astronauts doing these grand adventures, creating things that never existed before.

And these aquanauts doing the same thing. And I didn't latch onto, I want to be an X, you know fill in astronaut or aquanaut. I latched onto the broader point that there were these people whose lives were inquisitive and adventurous and innovative.

They were, you know, making things no one had ever done before and imagining adventures no one had ever done before and then making them happen. And that's what really grabbed me. It was – I want my life to be like that. And I just sort of figured somewhere along the way I'll figure out what that means I do.

Stan Grant: And when you say figure out what you do, you've been setting records and a series of, of firsts is what you've done. I want to come back a little bit later to the young Kathryn and look at how you saw the world and how you've taken, where you've taken your career, but I'm, I'm really fascinated by what the world looks like from space.

I think I read a description or heard a description once where you described it like as a, a beach ball or something I mean, what it looks like in that moment, when you look back and here is our planet.

Kathryn Sullivan: Your first glimpse of that, it will literally take your breath away. I promise you. On the very first moment that I saw it was eight and a half minutes after our rockets ignited at the Kennedy Space Centre and the engines have all just cut off, we're now hundreds of miles above the earth. Uh, we're about over England by the way, eight and a half minutes from the United States to England. Not, not a bad thing. And I, I should've had the discipline to stay quiet and just take it in, but I really couldn't help myself. And I just blurted out, “wow, look at that”.

Of course, it's still a very busy moment in the checklist and my boss on the flight, Bob Crippen waves his hands and says, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, not yet. Not yet. We're still busy. But it was that stunning a moment. So stunning that I risked getting demerits from my commander just eight minutes into my first flight.

And I promise you, it would have the same effect on you.

Stan Grant: Well it most certainly would. There are moments when you're allowed to lose your cool a little bit, I think, and that's one of them. But does it also strike you at that point, that is it a deeply spiritual moment as well when you look back at that and think that's, that's where we all are and I'm now here looking down at that?

Kathryn Sullivan: It certainly, it's awe inspiring I mean it's so remarkable both to be looking at that vista and you can see, typically about a thousand miles in any direction. And yet to be inside of the small cabin of a space shuttle, for example, and I think the impression that struck me the most in the moment was how crazy and wild and wonderful it was to feel completely normal and at home with where I was. And yet where I was, was in this extraordinary place.

That was like a little mental wave of cognitive dissonance that kept teasing, toying with me. And I remember one, one of our orbits, we were crossing from the daylight side of the earth to the night-time side of the earth.

And you could see the line, it's called the Terminator. You can see almost like an ink scribed line on the planet below you. The people to the right of that line still think it's daylight going to dusk and the people to the left – it's night. The spaceship is high enough that you’re still fully bathed in sunlight.

And it clicked at that moment that there could be a little girl down there right now on the dark side, looking up at the sky with their mother or father and saying, look mummy, there goes a satellite and she's pointing at me. And you know that sort of stunning reinforcement of the odd and unique vantage point you have, the extraordinary experience that you're having to be in that comfortable craft that you know like you know your home and yet soaring above the earth, hundreds of miles up at 17,500 miles an hour, the the magic and mystery and wonder of all of that never ceased to intrigue me and awe me.

Stan Grant: I love how you described that, how you normalise that because it's your office, isn't it? That's where you are working. It may be, it may be above the earth but you have a job to do.

Kathryn Sullivan: Right. And you know, think about working in your office or library at home and you realise, gee, I need a little more light or it's a little cool or hot in here, you don't hesitate about where's the switch, you just know how to do that. It becomes part of your normal every day. And yet that little microcosm of normal everyday going about my work has been transported to this extraordinary environment.

I always use the analogy of the children's book, the magic school bus. There's nothing magic about it of course, it's the marvels and the power of good science and good engineering that let you be in such a spectacular craft. And that allows you to be in a place that otherwise is totally lethal for you but gives you tremendous scientific opportunities both in the microgravity of earth orbit and the vantage point of looking back at, back at our planet from space, which is a hugely, hugely powerful perspective that, you know, we all make use of every day.

Even if, if only in such a simple form as our weather forecast. That's all enabled because of the perspective and the measurement power that satellites have.

Stan Grant: I just wonder if you could, to paint a picture for us, I mean we've all seen space films and movies about space and you see people going on space walks and there's that silence, and that sense of, of the vastness of it all the sort of eternity that people are sitting in. How accurate are those representations that we see in our films from what you experienced?

Kathryn Sullivan: Well any space flight scene that gives a sense of silence is not very accurate cause you’re living inside this machine.

Stan Grant: And it always is isn’t it, there's always this silence.

Kathryn Sullivan: Yes, if it's really silent, that means you're in the vacuum of space and it means you're already dead. So if you're alive and taking it in, you're inside a space shuttle or the space station or your very own body shaped spaceship. Which is really what a space suit is. It's just a one person, body shaped spaceship.

And so it becomes background consciousness you're not paying hyper attention to it all the time, but there are fans and pumps and motors that are running to circulate the air and the cooling and keep everything copacetic and comfortable for you – a squishy little human being that you are. So that does become background. And you can have a sense of quietude if you will, but it's not a quiet environment.

Stan Grant: I want to ask what you bring to that. You were in the first intake of female astronauts. What is the process of preparing yourself for what you need to do when you are eventually in space?

Kathryn Sullivan: I think what NASA tends to look for, or certainly what it seemed they were looking for at, at our intake back in 1978. An array of scientists and engineers and test pilots, a variety of scientific disciplines that were anticipated to be the focus of work aboard the shuttle for decades ahead. So they're looking for a level of mastery and accomplishment on those technical subjects. For civilians, a gate they set was to have a PhD and that was both about depth of mastery of subject matter, but also because in the higher education, the PhD hurdle is really one that you only get over if you get yourself over it.

So it's kind of a passage test of stamina, of perseverance, of self-direction, capability than the intellectual acumen to master a technical subject.

They were also, I think looking whenever they could find it, for people who had applied their knowledge in some fairly practical environment. So not all theoretical, not all just debatable, or hypothetical things but, did you succeed at building that telescope and making an observation of that supernova, yes or no?

In my case I had been going out to sea as an oceanographer since my fourth year of university, in ever more robust and responsible roles – far offshore so not easy to pop back into port if you forgot something. And so I think that experience gave them a good look at my ability to think ahead, to make an intricate complex plan and then to adapt and adjust.

How do you handle that? All the data you need for your dissertation may be on the line. Do you panic? Do you go bonkers? Do you stay focused? Are you able to stay a creative and constructive part of the solution? They're looking for life experiences, especially I think in the civilian academic folks that give them a lens on those personal qualities.

Stan Grant: What you're talking about is, to coin a pun, this is rare air that you are in, you are with other remarkable people. This is the Olympics, you are with the best, the brightest. What do you bring to that moment when you are there?

Kathryn Sullivan: Well, one of the things you have to bring is the ability to work through and around all of those interpersonal dynamics because you're not going to fly solo. You're going to fly as part of the team. And nowadays that team may also include people from different nations and different cultures. So, what you need to bring to it is a really solid and deep commitment to the mission, to the purpose. Mission over self to a fair degree. And the ability to either roll with the punches or tease each other or laugh through or whatever.

But the top line thing has got to be, you've got the commitment to mission first. We're used to challenging ourselves to excel or come in first or be the best. Most of the people chosen in the classes that I know well, really were more about challenging themselves to best performance not about knocking the other guy out or trash talking the other guy out of the way.

Stan Grant: You've read my mind I was actually going to ask that. You're going into space but you're also going into yourself. You are having to ask yourself very deep questions. Was that challenging for you? Was that intimidating?

Kathryn Sullivan: I wouldn't call it intimidating. I mean I had been doing things like that, again in field expeditions as an undergraduate geology student and the oceanographic expeditions I had been on since fourth year of university, those were good building block steps.

They were not as demanding in speed or in the high stakes as the space shuttle missions were, but they had begun to build those muscles that I needed. I kind of knew what that was like. I knew what it would take. Some of the hurdles stepping up to the speed and the scale of space shuttle flights were big hurdles and you had to dig a little deeper, challenge yourself a little more, find a different way to navigate with maybe a slightly different personality than you, but it wasn't intimidating it was just – this is what it takes to get it done.

Stan Grant: You mentioned before that these are, are competitive environments as well, and very ambitious people and people with their own agendas as well. How do you work through that?

Kathryn Sullivan: Well those sets of challenges exist as you work through a career in pretty well any organisation so you're gonna have to learn how to deal with those. I think in the space flight arena, and this is an ethos I think NASA had pretty well developed before we came in, so we learned our way into it and then became the keepers of it if you will.

It's about, we need the best idea for whatever we're doing on this mission so the competition can be around, what ideas do you have? How would you suggest doing it? But at the end of the day, one of the things that probably all of us had to wrestle with is now and then your idea won't win. You know someone else came up with a better idea. And if you've been really used to always being the bright kid with the best idea and getting the pat on the head, it might be that this time we're using Susie's idea, and now it's on you to instantly be okay with that because it's the better idea.

Stan Grant: Did that happen to you?

Kathryn Sullivan: It happens to everyone sure. Absolutely. So you put out the best ideas, you've got to lean in and be part of the creative and innovative process. You've got to be disciplined and objective enough that if you said X and someone else said Y and that looked like a really good idea that you too can say, that's the way to go.

Or if you know the more senior person says heard you all, we're going this way, you have to quickly put that aside. It's kind of like a professional sports person you need to quickly put aside the last play and move on to the next thing in fully, engaged, constructive mode. If you're going to pout or go into a snit or you want to exact some revenge on someone, we probably didn't select the right person. Which brings up one other point I do think these are the kind of qualities that the interview process in the selection was pretty well attuned to spotting.

Besides medical qualifications, the swing factor in that was about a 90-minute interview with a panel of 12 to 14 people who were all experienced space professionals, in our day – flight directors and senior astronauts.

So, they've seen plenty of everybody and lots of different types of people and getting you to walk through different experiences in your lifetime, including setbacks.

Stan Grant: I have to ask you about that interview process because what you're outlining there, I mean, you need to be confident, you need to be assertive, you need to be accomplished. But what you're saying there as well is the needs to be humility and honesty as well. And yet you really want to get picked. What was it like for you sitting through that interview process?

Kathryn Sullivan: Well, I figured I want to get picked. I decided it seemed clear to me I could do this job and I would like to do this job.

The third thing I saw clearly was I only want them picking the best qualified people they have. So I can't tell, I saw 19 other interviewees, they had 180 other people that I had not seen. I have no way of knowing if I'm going to end up in the top however many or somewhere in the middle, but I need them to pick me.

Not some actress, not some charade. So just go in there and be you. You know, talk things through, answer their questions as they genuinely come to you. We were the first batch of astronauts selected in about nine years. So there wasn't really anyone to call around and say, how does this work?

Stan Grant: So just quickly for our listeners, if you're like me and you're more of a visual person, jump onto our website, that's directionspodcast.com.au. You simply have to see the work NASA has done to map the scale and path of the smoke cloud over Australia during last year's catastrophic fire season, the science here is just mind-blowing.

In this interview series we have a hypothetical and I want to go into that now, this is a little bit different to the normal hypothetical it's hard to actually create a hypothetical for someone who has been to worlds that I could not even imagine, let alone go. But, but what I want to do is to take you back to the young Kathryn Sullivan. And you said right at the start it wasn't an ambition of yours to be an astronaut, but as we know the person we become is there in childhood. What was the young Kathryn like?

Kathryn Sullivan: Oh, I think the young Kathryn was a miniature version of just those same early astronauts and aquanauts. I was broadly curious, fascinated to try everything. Very active, sort of tomboyish we would say in the States, I'd prefer to be outside doing active things. I read from a very early age, earlier than my older brother did.

So quite the sponge, very, very broad and unthrottled curiosity, and parents who happily took the approach that – we're just going to fire your curiosity in any direction and support you exploring what that new interest might mean to you. So it was – oh, that's what you're interested in. Good. What can we do? How can we show you that? What would you like to try? And off you went.

So, I mean, the, the building blocks that I've been talking about that NASA was looking for in 1978, I think I can trace much further back in my childhood and attribute a lot of the early muscle development – in that sense – to my parents who were so, just encouraging, unfiltering of whatever you want to try – yeah safety guardrails where that might pertain, but outside of that – if you're interested in trying something we're interested in helping you and supporting you.

Stan Grant: When you start to enter the world, you've studied, you're you're coming out into the world and even though you've challenged those stereotypes, you've had that support, people haven't been able to steer the conversation, you still run up against that don't you, when you walk into all male environments. When the people making decisions are male, when the qualities that they look for in others may be male qualities or the eyes drawn to other men, how did you navigate that?

Kathryn Sullivan: Yeah, well I think my approach boiled down to, they can have whatever opinions they want, this is going to boil down to doing the job and performing. And some wisdom, I mean I'm not dumb about how organisations work so, go in some new setting and some new environment, especially as a rookie astronaut. You know, figure out who's in charge of that room or that meeting, and then you have to own your standing, own your position.

So, introduce yourself as the astronaut, as representing the crew. Uh, insist on that being taken seriously whether you think someone who looks like me should have that role or not is actually not your call. I do have that role. So you have to hold your own on those sorts of things. And yeah there were in particular and always somehow in the hygiene area was where you'd get the crazy and the hilarious consequences of decisions made by men about things that only women know, and those were usually just huge laughing stocks.

Can you imagine a bunch of 1960’s NASA engineers figuring out what women will need in their underwear locker on a space shuttle flight? How about you just ask!

Stan Grant: Seriously? So this is the sort of conversation you're having to navigate it, it's at that sort of level?

Kathryn Sullivan: There were moments at that level in field geology, we don't know where you will dress when we're just out in the field in tents and sleeping bags. And we don't know where you will, how you would go to the bathroom. To which my answer was usually neither of those is your problem. I know how to do both very well thank you very much.

Or research ships at sea, we'd, we only have two cabins with shared bathrooms, so we think that's all the more women we can have aboard. Really, no other toilet flushes if a female hand pushes the handle. I'll bet they all do. And you've toilets in your home that only flush if a man pushes the handle, I think it'll be all right.

Stan Grant: I love that idea of owning your standing. And I was very conscious at the start of the interview that you are ‘Doctor’, and that those titles matter.

Kathryn Sullivan: It's less important to me egotistically than it is in terms of social and organisational factors. So if you're introducing a panel of people – three men and a woman – and you introduce the men as ‘Doctor’ and ‘General’ and ‘Admiral’, then you may not introduce me as Kathy.

If you introduce everyone as Stan and George and Ralph and Kathy, you know, that's fine. So parity, equity and that kind of treatment. When I've been in charge of organisations and had roles of defined responsibility – payload commander on the space shuttle, Navy commanding officer, head of an agency – a bit of wisdom that I learned most of all from our Navy is, you have to protect the billet.

So, you're commanding officer of something or other, it must always be the case that everyone around you understands and respects the authority of the commanding officer of the ship or the head of that agency. You may encounter someone who's not convinced that they should respect you because you're the first female or a person of colour or somebody odd, and again, go to the bar and have whatever opinion you want about me. You will not ever fail to salute the commanding officer. Period.

Stan Grant: It's about separation too isn't it? There is the person and there is the office, and when you are talking to the office, that is critical isn't it?

Kathryn Sullivan: When you are assigned, and gain roles like CEO, agency head, commanding officer, many, many different ones, you owe it to the organisation, you owe it to the effort that that's a part of to be sure that the ecosystem that's been put together to achieve that purpose can function.

So even if you don't, you know, ego wise, feel I really have to have all this. You have to be sure you're holding up your part of the bargain in the team, in the organisation.

Stan Grant: And you have gone on of course to positions of leadership in the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, which you were the administrator of. You were Chief Scientist of that as well.

Kathryn Sullivan: Chief Scientist and Deputy and Administrator, sometimes all at once.

Stan Grant: Tell us about that role and what you brought to that role, the importance of that role.

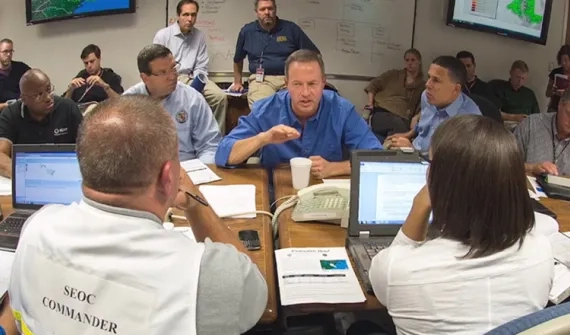

Kathryn Sullivan: So NOAA as we shorthand that agency, it's the oceans and atmosphere agency in the US government with the focus completely on environmental intelligence. So, take the pulse of the planet, make billions literally of measurements every day of the atmosphere and ocean conditions, and use those to make everything from weather forecasts to fisheries, catch outlooks.

It spans a huge range from satellites to aquaculture farms and marine biodiversity. The official governmental title of that, the second title that goes along with the post by the way, is undersecretary for oceans and atmosphere, which as an earth scientist, to get a title that actually says I'm in charge of oceans and atmospheres – kind of pretty cool.

So it's several different operating units under that umbrella that each do their bit of the work and then have to collaborate and cross strap amongst them to produce the weather forecast, the fisheries outlooks, the drought outlooks. The information people from head of household to heads of state use to keep their population healthy and sound.

Defend or protect or protect people against, and communities against natural hazards, forecasts and warnings on typhoons, hurricanes, tornadoes.

Stan Grant: And I know that you've, you've said this in the past and I'd never thought about this really until I heard you say it. We are the, the first generation that can map this place that we live, from space, from the oceans, and we can collect that data. How important is this information, this geographic information systems, in being able to do just what you said, a practical application to have an impact directly on our lives.

Kathryn Sullivan: It really is vital and it's, it really is a consequence primarily of the space age. Because satellites that circle the earth at 17,500 miles an hour with the right instruments aboard can make billions of measurements per day of the whole planet.

It's the, the space age is the first time in human history that you really can say, we can take a snapshot of the entire planet, the distribution of moisture in the entire global atmosphere, essentially, now. Temperature on the ocean surface everywhere on the planet, essentially, now. That's thanks to satellites. And that ability to get that essentially instantaneous snapshot, this is the state of the planet right now.

Those are the data that let you run computer models that allow you to forecast or predict ahead. Well what will it be like in 24 hours? What will it be like in two days, three days? Is there a typhoon somewhere? Where is it going to be three days from now, four days from now?

Can I prepare for that? Can I evacuate people? Where should I stage disaster supplies for the aftermath? That foresight about conditions that have yet to occur is completely novel in human history. And it's quantified, it's global, it’s a consequence also of sharing among nations with these measurements and the systems that enable these capabilities.

Stan Grant: It's also, as you say, practical. Let's look at one example here. We've both – in your country and in mine, in the United States and in Australia – we've dealt with enormous wildfires, bushfires, which have been devastating. Australia's fires last summer captured global attention because of the size and the catastrophic impact.

How do you apply this knowledge, this mapping, to a situation like that, that someone in that moment can use to find something, to find an escape route, to find water, whatever it may be?

Kathryn Sullivan: That question has several scales of answer. One is, if you're living in an area that's prone to it if you're one of the firefighting teams, this satellite forecasting capability that I just mentioned, that's what gives you the one or two day ahead outlook of dangerous fire conditions are going to be Wednesday, Thursday, Friday – maybe a break after that.

On the ground during the event, there are satellites with fine scale enough sensors that they can help the frontier firefighters see where the fire line is, track it and monitor it. Some of those sensors also are put on airplanes to get a finer scale of view from a lower altitude.

And then all of the, that data and information measured in real-time, gets added and plotted onto topographic maps. So the emergency response authorities commonly have that kind of look at things that they use to shape their evacuation orders. We're not yet at the point where I have weather and hazard information on my cell phone as readily handy as sports scores are today.

Stan Grant: But that's where you're heading. That's where you want to be.

Kathryn Sullivan: That would be my vision. I want you to have the earth in your pocket.

Stan Grant: Wow. I wanted to bring this back to the questions of leadership and your life has been so much about achievement and the achievements are remarkable. When have you failed?

Kathryn Sullivan: When have I failed? Well, I could give you a long list of highly embarrassing mistakes, but I mean, abject fail, everything falls completely apart. I've had moments of feeling that way sometimes, but that just, when you look further back along the history, that's just a kink in the road that you hadn't planned to go down.

I was running a small museum here at my hometown some years ago for example, and we went out to the public with a ballot issue to shift our funding model so that we'd have 10% or so over a budget provided each year out of a tax levy.

And, it's not a popular thing ever to ask, it was pretty important to us financially at that point in time. And of course I had to be the spearhead, the figurehead, the flag bearer for that whole campaign. And it failed badly. We didn't get the result we wanted. The voters said no, but you know we already had a plan B drafted in hand.

It was very clear to me the organisation I was leading would be fine in the long run. It was either gonna go down this path which would be a little smoother and easier, or go down that path which would be much harder. But there was no way there was not going to be this institution five or 10 years down the road serving the community well.

It's just the question of how rough a road we were going to have to go down. It was a devastating loss to me personally. It was really hard to lead on through the next couple of years and get onto that rougher road. But my vision was right. The place is still up and running and doing fine, barring the pandemic and its consequences.

Stan Grant: And it can be good to fail. We can learn enormous lessons out of failure. What advice do you then offer, some really tangible examples of what leadership is, how we learn from failure, how we rise to challenges, how we adapt. What are the things that you would pass on to someone aspiring to that leadership?

Kathryn Sullivan: Don't quit. If all else fails, do the single, next, most right thing you can see. Celebrate that small victory. Go to bed, get up in the morning and do it again. And there's just a really bleak moment and everything seems lost. Just that. Don't go to a standstill. Take one next step. Just do the best right thing you can see at the moment, it will be enough, and then keep going and keep going.

And the, you know, the fog will clear, the lights will come back on. You'll find your way forward.

Stan Grant: But I suppose we all have moments of doubt. How do you overcome that?

Kathryn Sullivan: Do the next best right thing you can see. I mean, you just really have to keep going. If you've got supporters or people around you that can help sure you up or pat you on the head, you know shift your perspective a bit, that's wonderful. But sometimes, you know everyone goes through some bit of a wilderness period through life now, and then from, you know, the grandees like Churchill to the, everybodies – like all the rest of us.

And sometimes that, you know, digging deeper into your fundamental principles and values and recentering on those. Sometimes that's what reinforces your foundation and gets you back to where you can take that next step. And then the next one after that.

Stan Grant: So just on those principles and values that you've learned from childhood, but you've also gathered along the way, and now looking back at a lifetime of achievement with so much still to come. What would you say to the young Kathryn from where the Dr Sullivan sits today?

Kathryn Sullivan: No one gets to edit what you're interested in. No one gets to edit what you're interested in and no one can foresee any better than you can what that may become and where that may take you. So, you know, it's your life you're building. Life is not a performance like reading some script – pre-existing script. I always liken life to laying a sidewalk of bricks. It's one brick at a time, and it's not – sometimes not entirely clear which way the sidewalk is going to bend, but it's your sidewalk.

So, one brick at a time, one job at a time, one class at a time. Make that the best brick you can put it in the sidewalk as best you can see. You might now and then have to go rip a couple of bricks up and adjust a little bit. That's life. It's a building. It's not a performance.

Stan Grant: It's been a really fascinating conversation. And I really wanted to finish with this question to you. And it's, what affected you the most? If there is the one great memory, which one would it be?

Kathryn Sullivan: Oh, I think I would have to take the – that very first moment of seeing the broad panorama of the earth from orbit. That was just so unexpectable. And you're talking to someone who had probably looked at every single photograph of the earth ever taken by any astronaut anywhere before she got into the space shuttle for her own first flight. And even having done all of that, it was so breathtaking.

Stan Grant: I'm so envious Dr Sullivan, I mean few get to do that. I don't think I'll ever get the chance in my life but, you know, thank God people like you have. And you've been able to tell us that, and we have those incredible images of our earth. It's been a real pleasure to talk to you. Thank you so much for being really generous with your time.

Kathryn Sullivan: My pleasure Stan, it's been a delight.

Stan Grant: Dr Kathryn Sullivan.

And for more resources, including a number of articles from Dr Sullivan from her time as an astronaut and also at NOAA, visit directionspodcast.com.au.

Our next episode features criminal profiling expert Mike King. Someone who spends time with serial killers in order to understand exactly how they think and act.

Mike King: You know, guys like you and me we don’t know what it’s like to fantasise about killing somebody, but we certainly know what it’s like to fantasise about being successful in our careers, or other things so we can vicariously begin to understand, because what we’ve found is, these serial predators are in pursuit of legitimate kinds of needs. But the difference between them and you and me is that we go about it by legitimate ways.

Stan Grant: Mike King, coming up on the next episode of Directions. If you're interested in true crime and stories from Mike's career, search for Mapping Evil in our podcast app now.

This is a Boustead Geospatial Technologies production. This episode was the narrated by me, Stan Grant and Dr Kathryn Sullivan.

Sound engineered by Nearly Media and Deadset Studios with editing support from Kim Douglas and Sydney Podcast Studios. Artwork by Superscript and our Executive Producers are Alicia Kouparitsas and Raquel Jackson.

If you like our show, please give us a five-star rating. Leave a review and be sure to tell your friends. Follow us on Apple podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also download a free trial of Esri software, check out our show notes and access other resources at directionspodcast.com.au.

The views and opinions expressed in this podcast are solely those of the participants and do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of Esri Australia, its subsidiaries or partners.

Hypothetical scenarios presented as part of this episode, are purely fictional, and while they may draw on current issues, they do not depict the actions, values, or beliefs of any specific individual and/or organisation.

And finally, this production would not be possible without the support of Esri Australia.

VIEW TRANSCRIPT

VIEW TRANSCRIPT