The proven formula for driving digital transformation at a global scale

Brian Boulmay is on a mission to democratise data. He believes multinational companies can create greater efficiency, accuracy of insight, and collaboration if they share data sets.

During his tenure as the Global Integration Director for BP, Brian Boulmay developed the award-winning OneMap system; a one-stop shop for geospatial information and analytics used by more than 70,000 staff across the world.

Boulmay is driving a radical approach to transparency. He shares his tips on leading teams towards a more collaborative way of solving problems and adding value to projects and businesses through shared information.

“That's the beauty of geography, right? Regardless if you're the person drilling the well, the person dealing with the environmental permits, the person dealing with the construction and engineering, you all need the same core information. All of the information that was shared, we centralised and managed it once, so that many parties could use it.”

Never miss an episode of Directions with Stan Grant - subscribe now.

Featured in this episode

Subscribe to hear how other leaders are using cutting-edge mapping tech to solve global challenges.

- Click to view the episode transcript

Brian Boulmay wants multinationals to share their information

The power of “one”

Brian Boulmay: We had a saying in the company, for any large program it's ‘people, process and technology’. And it was in that order on purpose, people first. Then you bring in the process necessary, and the technology is really just a supporting element.

If you get the people to understand how they're adding value to the business, you show them how they're driving some of that bottom line impact, how they're helping the business solve problems. People will follow. I mean, we've used a lot of these core technologies, literally for decades, we were some of the first industry to really get into geographic technology, but to use it at this scale. This was new.

Stan Grant: As data becomes more ubiquitous, the sharing of this data across organisations, political arenas and countries is increasingly vital, but not every company wants to share information with say, their competitor. And yet Brian Boulmay’s done exactly that. As a global leader with multinational corporations like BP and Shell, he's introduced a radical program of transparency, creating open access to publish data, to solve complex problems across a variety of sectors.

On Directions you'll discover how Brian Boulmay has established a culture of collaboration with data systems. So everyone has the technologies at their disposal to ensure the decisions they're making are the right ones.

Support for this episode comes from the country's leading mapping technology and services provider, Esri Australia. To learn more about how Esri tech is supporting the world's most progressive leaders visit esriaustralia.com.au/trailblaze.

Hello, welcome to Directions. I'm Stan Grant. We live in a world that's increasingly small. We can connect with people in ways our predecessors would never have even anticipated. We live in a world of information and big data, and that's made us more efficient, but it's also made us approach this world with a little bit more trepidation and made us reserved about how we share information and with whom.

So, how do we deal with this and how to big organisations best incorporate technology and the use of data into their operations?

Brian Boulmay is a leader who's built a global reputation for digitally transforming some of the world's largest petroleum enterprises, including BP and Shell.

Welcome Brian.

Brian Boulmay: Good morning, Stan. Great to be here.

Stan Grant: What attracted you to the idea of, you know, if I can use that word harvesting, I suppose, harvesting data and using technology in more efficient ways?

Brian Boulmay: I think it's the creativity element because you mix a bit of the technology and the science, but then you get to apply it in creative ways to solve problems.

And that's fun because you get to take something from the beginning and figure it out and end up with a solution in the end. It was like little puzzles every day.

Stan Grant: Were you always that way inclined? Is that something that, you know, from childhood, is it numbers? Is it information? What is it that attracted you to this?

Brian Boulmay: It's definitely not numbers. Not a big fan of math. It's more of the, more of the building and delivering of things. I used to enjoy building forts in the backyard, you know, set a plan, put it together and end up with something finished in the end.

Stan Grant: And now you're working in a much, much bigger fort.

Tell us about, about how you approach this in an organisation like BP, of course, where you had a long career, a massive organisation, more than 70,000 employees. I don't know how many countries, but 60, 70 countries, maybe around the world. How do you approach using this sort of technology and data in an organisation that is as enormous as that?

Brian Boulmay: In a company this size, you have to sort of balance sustainability and cutting-edge. So we worked very hard to put a kind of core platform in place that is the kind of foundation, but we built it in a way that we can then drop in modules on top quite quickly to solve specific problems. That allows us to scale to a company this size and across the number of countries and, and types of businesses that we're involved in.

Stan Grant: The phrase that is used a lot is One Map. Explain One Map.

Brian Boulmay: So One Map is just an internal kind of brand if you will. When we started this journey, we had lots of different systems that were trying to be our mapping technology.

Very difficult to move data between those systems to get consistent results across those systems. And so we had this mantra and this sort of emerged early on about getting to ‘One Map’ and that became the name of the program. And program of work that is, and it's a, it stuck ever since it'd been going nine years now.

Stan Grant: So one of the things you would have no doubt have had to deal with was the idea of centralising data and information. Yet at the same time acknowledging that people don't work in the one place, people don't live in the one place, the issues that people have to deal with are different. You're dealing with different geographies, different governments, different regulations, different laws, different languages, different cultures.

So how does One Map work in a diverse organisation in a very complex, and diverse world?

Brian Boulmay: You've picked up on, on a key topic. So, it is One Map in terms of one system, but we actually deployed it in a very federated way. So we put systems into every country that we operate for that very reason. We want it to be personal to those users.

We wanted to be focused on their base information, their regulations, their operating environment. And so even though we did it, the core technology footprint exactly the same, the use of the platform in each country is actually a bit different. And the problems they solve are a bit different. It could be a solar farm in one country, it could be drilling in another country. It could be logistics and routing network and in another. Same core platform, total different use cases and different, installations for each of those entities.

Stan Grant: How do you centralise that? How do you, how do you adapt to what are very different circumstances and different ways of working, but also centralising all of that information?

Brian Boulmay: So that's the beauty of geography, right? So regardless of if you're the person drilling the well, the person dealing with the environmental permits, the person dealing with the build out of the construction and engineering, you all need the same core information. You need the bathymetry you need the topography; you need the political boundaries. You need the road network, the electrical.

All of the information that was shared, we centralised and managed once so that many parties could use it. And then we allowed each entity to then maintain just a much smaller subset of data specific to their process or their project. And that again, allowed us to deal with massive global data sets with a very small team, do it once and serve it to the whole company, and then allow smaller teams in that asset or in that region to solve those local problems with their local data sets on top of those base information.

So think of it almost as like the Google Earth for the company, right? All the base map information is there. And you just go in and add your extra bits on top.

Stan Grant: I'm really interested in the word that you used there “share” information, because that then says to me that this is something that people bring to it and that you're able to pool information and resources. How do you do that?

Brian Boulmay: We built a very flexible approach where global data and data that wasn't confidential, it was just shared completely across the company. Individuals could then publish their own data on that same platform, and they could restrict it to just themselves or to their team or to their business, or they could share it also globally.

And by giving them those options, the people that were still sort of scared to let their data out if you will, they could still leverage the platform, but keep their data restricted. But for those that didn't have confidential issues, they could share with the whole company.

And it's really that sharing that drove the growth we've seen and the use of the system, because every data set that goes on, every use case that solved, is something that another region or another business can pick up and use.

Stan Grant: Were there trust issues because, you know, that's one of the things we really run up against in this world of big data and sharing a lot of information is how much you are willing to give over and how much of your own personal sovereignty I suppose, or how much you are prepared to surrender. And then what happens to that information? Does that go to building layers of trust in the integrity of the people and also the integrity of the systems that you're operating?

Brian Boulmay: Trust was huge in the process trust in the platform, the fact that it was going to stay, it was going to sustain, it was going to meet the business need and then trust in others using and sharing your data. And we come from an industry that historically people would hold onto data. It was kind of their value. They saw it as their value to the company. And now we're asking them to, to publish that and share it with everybody.

And in the early days that was difficult, it really was. But once you got a first few to sort of take that step and start sharing that content and letting people see what they were doing, it just became an avalanche of users because now everybody wants to try to look as good as that last one and do as well as that last one.

So it almost became the reverse, people actually almost got competitive and trying to make the next best solution.

Stan Grant: I'm interested in that and when you say it was difficult in the early days, as someone who is a leader, because this is not just expertise you're talking about, but it's leadership. So what do you bring to that as a leader to deal with some of those difficulties or resistance?

Brian Boulmay: So our approach was transparency and walking the walk. So the early stuff that our central team did, all of it was transparent and published and shared to the company – even the smallest of projects to the largest of projects. So we were sort of the first ones seeding the farm if you will, getting the ideas out there, getting the examples going and that helped people come on board and start to trust as well.

And you also have to work the people side of this right, technology doesn't solve everything unless you bring the people along. And so we found the champions, the people that were interested in doing cutting-edge stuff, pushing the envelope a bit, and we helped them get their first few successes, which of course gave them confidence, got them talking to their peer groups, which then brought on people as well.

Stan Grant: Yeah, I'm really interested in that because this is something that you've repeated and things that I've heard you say that people are more important than technology. Explain that for me, because we can live in a world where you can disappear as a person. You can have a technological sort of fingerprint.

So how do you, how do you balance that? The technology and the people, because you have said this, that the people are more important.

Brian Boulmay: Yeah, the people are definitely the most important. So we had a saying in the company for any large program, it's people, process and technology, and it was in that order on purpose. People first, then you bring in the process necessary and the technology is really just a supporting element.

And if you, if you get the people to understand how they're adding value to the business, you show them how they're driving some of that bottom line impact, how they're helping the business solve problems. People will follow. But you have to give them something to follow. They won't just trust in a empty system, right?

They need to see examples. They need to understand how it impacts their business. So we spend a lot of time educating them, providing training for them, showing them how they could work better. We've used a lot of these core technologies, literally for decades. We were some of the first, the first industry to really get into geographic technology, but to use it at this scale, this was new.

It was a new way of working. It was a new way of publishing, a new way of sharing. And we had to bring those people along with that.

Stan Grant: And Brian, one of the phrases that we hear a lot, and I know that you've talked about this as well is this idea of democratising data and also valuing people and people's input.

So how have you seen that change the organisation in terms of making it more, I think you used this word earlier as well, being more transparent and more accountable and more democratic.

Brian Boulmay: Absolutely central. It was, um, when you get data out there and you get data out there that you can trust even bad data is good data, as long as you know, it's bad data.

So you can present the data with the right metrics so people know what they're using and you make the same information available to everyone. That transparency and that sharing of information, you basically unlock the full brain of 70,000 people versus before it might've been a team of 10 or 20 working a problem.

And so you get everybody interested and everybody engaged and everybody coming up with creative solutions. If you centralise it too much and lock it down too much, you're at the limit of the, of the brains you have in the room for that.

If you open it up, you allow everybody that has something keeping them up at night to come back and tinker with the system and look at the data and understand their problem. And actually come up with a creative solution, a central team using a lockdown dataset may never uncover.

Stan Grant: Yeah and you must've seen enormous change as well, I mean you mentioned before GIS, for instance, I mean, that has been transformative, hasn't it? How have you seen that change? And when you talk about One Map, I mean, clearly that's absolutely critical.

Brian Boulmay: Absolutely. So in early in my career, almost all GIS was done on a desktop. And on a desktop, you meant that meant data on somebody's C drive, data on somebody’s, maybe network share, as we've moved into the more modern technologies, the big data stores, the service-based architectures, the rest end points.

I can now have an individual sitting in Houston, publish a dataset that's instantly available to somebody sitting in Jakarta, Indonesia just seconds later, just as simple as it is on your iPhone. Using Google maps to find the nearest coffee shop, we have that same capability with our assets globally, on the digital map.

Stan Grant: In a practical sense, how do you see the benefits of this and the benefits of this beyond your own company or your own people as well? I think one of the examples that I've heard about is the, is the flood app and how that's utilised and how that's accessed by others as well. Take us through that.

Brian Boulmay: Yeah. That was an interesting accident. We had our internal people, used to get up and drive to the office at four in the morning. And they had a whole room of monitors where they had weather up on one and flood information up on another and traffic on another. And they would make a decision whether they were going to open or close the office for the day.

Cause we had 6,000 people moving across Houston and once flooding starts, you don't want to be on the roads. So BP would try to make a decision very early to let people know whether we were going to open the office or close the office during a flood event. As the technology evolved our way of approaching this evolved, and we put together a simple app that those same crisis people could just roll over in bed and pull it up on their iPad and look at it and make their decision.

They didn't have to drive to the office and get in front of all these computers. And we put it all into a single app so they could see the traffic, they could pull up the traffic cameras, they could see the weather, they could see ways information for flooded reports, et cetera, everything they needed to make their decision.

And then we were also able to add in where our people live. In Houston we're very flat and if the rain hits a certain part of the city, one part of the city may not be able to travel. But the other part of the city's perfectly fine. The crisis team can go in and just circle, this is the area that's impacted and immediately give them a count of employees that would be impacted to travel.

And if that number is above a threshold, then they closed the office. As that evolved and we made it available outside, some of our peers in industry said, ‘Hey, you know, can we use that?’ And we're like, well, there's nothing proprietary in the data other than the people, of course, we took that bit out, but all the other information, we just opened it up to the public internet.

Um, and it ended up being used by several of our peer companies. Even as well as the red cross and helping navigate people to shelters during flood events. So the app became very successful and it's still alive today.

Stan Grant: We've talked about the positive aspects and all of our lives are immeasurably enhanced and changed because of the capacity to carry your world around in your pocket in a phone, but, but it does go to that idea of how we protect information, Brian, and, and we know that we also live in a world where it is highly competitive. There are greater geopolitical tensions in our world today and data is its own battleground.

What challenges does that present for you in being able to protect the information that you have in a world where people are finding increasingly new ways to be able to, to access it?

Brian Boulmay: Cybersecurity is key and centre in our efforts and everything that we publish and everything that we create, we have that in mind. So the systems have gone through rigorous testing the technology, the core software that we use, has gone through that same sort of testing.

We have regular spot checks and from a data perspective, if every bit of data is classified in terms of whether or not it's considered proprietary or confidential or secret or open. And open data, of course we can publish, you know, however needed, but if you're in any of these other classes, then you have to go through extra checks and balances to make sure you're not accidentally sharing that data with the world.

Stan Grant: Now, if like me, you're keen to see Brian's One Map in action, head on over to the website, directionspodcast.com.au. There's a two-minute video explaining how this system works plus Brian shares his top eight lessons from leading BP's digital transformation.

Okay Brian, this takes us to our hypothetical. I love this part of the podcast because it gets fun, and we can simulate a real-life situation and allow you to bring what we've discussed here. The way that you collect information, the way you use information, questions of trust, control, security – all of those things.

And this is the broad hypothetical we're talking about… Now a commercial airline has crashed into the ocean of the Northwest shelf of Australia. A very close proximity to one of your company's offshore rigs located in a geopolitical hotspot as well. And the location of the crash is well within the 12-mile exclusion radius, typically surrounding rigs.

It's not known at this point what's caused this. Is it just an accident? Is it an act of terror? Is it something more suspicious like that? There is a risk of significant debris from the crash, and that may have an impact on the oil rig as well. There are concerns around the location condition of crash victims, workers on the site.

Of course, there are questions about environmental damage and even risks of an escalation or explosion from here. The plane itself is sinking in the area. There’s a lot of risks that if a pipeline burst there'd be an uncontrollable release so there’s multiple things that you're dealing with here.

You're the leader of the disaster response unit for the company. What's the first thing you do?

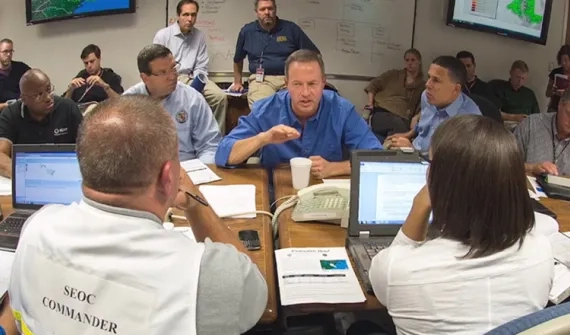

Brian Boulmay: So the first thing we do, we call it the five-minute map. So anytime there's an incident, anytime there's any sort of hazard or a call that comes in, we want the five-minute map, which is, where is it? What resources are in the area, what resources might be at risk and where are our people where are assets?

So that's the first thing we do is we build that five-minute map. The next thing we'll do, if we are going to activate a response team is we will notify the tactical response team, the incident management team, and then usually calls into of course corporate office to let them know that something's underway.

We tend to deal with emergencies local first and then call in help as needed from the rest of the company.

Stan Grant: Now, as I said before, you're dealing with a situation that that's fast-moving here and you are having to access both your central information and also deal with the things that we discussed before, the geography, the different political climate.

We know that this is also in a geopolitically sensitive area. How do you deal with all of those factors as well? You're not dealing with just one particular set of circumstances or one particular jurisdiction.

Brian Boulmay: Absolutely, so every operating area, especially if the plane has gone down that close to one of our facilities, we have emergency response plans in place. Not usually for planes, but for other potential problems that could happen.

With that we will have the, the governmental entities that would be the responsible party. So in the US waters, that would be the coast guard. In Australian waters, there would be an agency that would be tagged to. If there's another geopolitical area nearby that this contested, we would probably be notifying those governmental agencies as well.

As we put together that response team, quite often that's on the ground running, as you said, this is happening fast, right? It's not going to wait for everybody to show up. And so we actually have something we call the ICS, an Incident Command Structure, that goes in place right away. And all those notifications start happening.

There's teams set up that are, that are set for that. The technical teams, the mapping teams for instance, they get after the problem. Right? So while the incident commander's making notifications. The mapping teams are getting out there and saying, okay, where is this? What's in its way? What might it hit? What possible risk is there?

And we look at, at any situation like this, also kind of in order, people, environment, company. So we want to make sure people are safe first. So we're trying to figure out where all of our people are. So we'll be bringing up maps of any vessels in the water we'd bring up maps of any subsea work that's going on.

Most of those things we track real time, so we'll know exactly where those people are. Next we'll be looking at the environment. So it will be looking for sheens on the water. Is there, is there a fuel spill, is there, is there something that needs to be dealt with from that perspective? And then third, we look for risk to equipment, risk to our assets.

So is, you mentioned it's floating, some of it’s sinking. So is the tide coming towards us as the tide going away from us, that'll be on our maps. What's the depth of the water? What's the size of the pieces? Et cetera. Is there damage potential?

Stan Grant: One of the things we like to do in the hypothetical is to throw a spanner in the works if you like. You're moving along with all of that information and you’re very confident, Brian, in the way you're going through this, because you know this, you know this so well. And you have command of the data and, and the processes, but you've now just learned from Australian intelligence who is sharing with you, that they had heard that there was a risk of a terror incident and they are now treating this as an act of terrorism, that someone had hijacked this plane and this plane had been brought down specifically in that area.

Now, what do you do? How does that change what your approach is from here?

Brian Boulmay: So, I mean, that potentially changes everything. Our people offshore aren't trained to deal with security issues like that. And so we would immediately start to activate security type forces or military from the local government to assist in this, because if it really was a terrorist situation, you don't want to be sending a group of responders in on a boat.

And all of a sudden, they're faced with people with weapons or some other problem, because then you've escalated the problem, right? You've exposed more people to harm.

Stan Grant: And here’s another twist. You've also just learned that…

Brian Boulmay: I thought you said this was supposed to be fun! I think it's fun for you.

Stan Grant: It's fun for me. It's fun for you too, Brian I know you enjoy this. But here's another thing you've also from intelligence that they believe that your systems may have been compromised here.

And they're worried now about what this particular group knows about your own operation. This wasn't random, this was a target and it was a target that BP or you or whatever organisation you're representing, but it was targeted and that they believe they have access to information. This raises concerns in a One Map world about other incidents in other places.

What do you do now? And you're also being asked questions by the media about where did you go wrong?

Brian Boulmay: So that would be one of the calls you would get that you have would want to verify, obviously before you respond to. If we did think there was an information or system breach, the offshore facilities are actually fairly well disconnected from the corporate environment, given just the nature, and the distance from shore, et cetera.

So more than likely we can just cut off resources immediately. But what I'm assuming the digital security folks would do is they would just, they would turn on the extra level of watch on any sort of comms coming in and out of that pipe to make sure that there's no information being pulled or pushed from that platform.

One Map is mostly served from onshore, so I wouldn't think that there would be any One Map information at risk on the platform. It would mainly be operational elements of the platform itself. But if that was the information would we be receiving obviously our next call would be to our digital security teams.

Obviously, a big company we have teams like that, around the world that are constantly watching our networks and watching for any sort of penetration and error problems with the system.

Stan Grant: The the good news is Brian that, you know, this, this situation is resolved. It was a one-off and your people were safe and the crisis eventually passes.

What are the processes here in terms of what you learn from a situation like this?

Brian Boulmay: Ah, excellent question. So every drill and every real world event that we respond to, we have what we call a 'hotwash'. So everybody involved in the response comes together at the end, and we work through what we learned, you know, what did we do right? What do we not do right? What do we need to know for the future? And all of that information actually goes into a knowledge base that all of us can pull on when we go into the next response.

And it's absolutely crucial to capture that in the heat of the moment. If you let everybody go home and you know, you start deescalating and you kind of forget the details. Cause there's always learning in any sort of response and you want to capture that learning cause you want to make it easier the next time. And that could be technology changes. That could be data improvements that could be, you know, process improvements. And you want to capture all of them to ensure you're best prepared for the next potential scenario.

Stan Grant: Okay hypothetical over you passed Brian, that was fantastic. I wanted to finish up with just a bit of discussion about leadership because so much of what you've talked about is, and even the language that you use it is sharing, accountability, transparency, trust. It is very collaborative. And I just wonder whether that goes to your leadership style. So how do you approach leadership in this environment?

Brian Boulmay: So absolutely it's a team player scenario. So in the geospatial world you have data experts, you have development and scripters, you have cartographers, you have the data science guys that really get into the numbers. Each of them are really good at what they do. Very few people possess all of those skills.

So one of the things you do to have a high performing output is you put together a high performing team. You find the people with each of those set of skills that they're really good at their piece. And you bring those together into a squad that can basically take on anything.

And that, it's just amazing when you get the right set of people together, what they can achieve. It is all about the team.

I guess that's my leadership style is, you enable the people around you, you let them develop the skills in their core areas. You let them expand into their fringe areas. But when the rubber hits the road and you have a problem to solve, you put the best pieces together to generate the whole.

Stan Grant: And I suppose there are lessons to be learned here aren't there for others. You've been a pioneer into this brave new world. You've seen the world change around you over the extent of your own career. So, what are some of the takeaways for other people who are approaching this, and God knows what sort of world we'll live in 10 or 20 years from here things are changing so quickly.

What are the advice that you would offer to people who are working in a rapidly changing world in a high tech world and dealing with all of those things that we've discussed?

Brian Boulmay: So many people say I don't have the right data, or I don't have the best data, or I don't have the exact tool for this or that.

The reality is in most cases, your company is already dealing with a problem. They're already using the data set that's available to them. They're already trying to solve whatever it is. And so maybe that data is good enough to just get started. I've seen a lot of companies really get tied into data model activities and trying to create the perfect data.

Data's never perfect, by nature it's not perfect. It's constantly evolving. And so just start with what you have, because you might be surprised if you can unlock all the other brains in the company, they're going to take that data good, bad or indifferent. And they're going to come up with new ideas as a group that you're then going to be able to improve upon.

And then when you hit critical things where you need that absolute perfect data, deal with that in that way, but all these other areas that it's okay to flex a bit, let them flex, let them get out there and solve problems. And the tech, just the pace of tech, there are no more, build it perfect, and then deploy it.

It's you're basically building it as you go. The systems are upgrading every two weeks. The data's changing every, you know, every day. You have to go with that flow and just make sure you've got good people that are making good decisions along the way.

Stan Grant: And what do you look for, if you are looking at the next Brian Boulmay, the person who's going to take what you've done and take it to another level. Who's going to be that next generation of leadership. What do you look to identify?

Brian Boulmay: The key skill for me is probably curiosity. I'm looking for the person that's always questioning is that the right way? Is that the best way? Can we do it this way? How can we solve it like this? The person who's actually looking for that next step is going to uncover the next big thing.

The person who's, you know, show me the manual and I'll follow the steps. That's really not the kind of person that's going to take you into the next world. Right? So we want the people that are curious, the people that are pushing the envelope. That are still taking care of the core that needs to be taken care of, but always pushing to continuously improve.

Stan Grant: Listening to what you've been talking about and going back to the hypothetical as well and how you ran through that reminded me of something that Mike Tyson, the world champion boxer once said, “Everyone has a plan until they get hit”.

What you're talking about Brian is, is precisely that. It is, it seems to me, it's about preparation. And then when you do get hit, you've got things to fall back on and that you can stay calm and that you can make crisis decisions with the information at hand. So it's personal qualities, isn't it that you're looking for.

The ability to stay calm, the ability to adapt, to think laterally, but also it comes back to the quality of the data and the information at hand and how much you trust in that doesn't it.

Brian Boulmay: Absolutely. We said it at the beginning, people, process and technology. You get the preparation in place. You get those foundational elements in place, you can adapt to any system or any problem that comes along. And, um, if you don't have one of those pieces, right, you're going to struggle.

Stan Grant: Brian, it's been a real pleasure. Thank you so much. It's I feel like I come from another generation in some ways it's sort of a world that's still foreign to me and I'm sort of finding my own way, but it's the world that that we live in and it's been remarkable to be able to pick your brain and to be able to share that with you. Thank you so much. And thank you so much for, for playing with us with that hypothetical as well. It's been a real pleasure, Brian.

Brian Boulmay: Absolutely. It’s great. Thank you very much.

Stan Grant: And if you'd like to learn more about the digital transformation project that Brian has spearheaded and talked about today, including that One Map system then visit directionspodcast.com.au, and there's some great videos and case studies up there from Brian. And of course, a free trial of the Esri technology he used to create One Map.

That's the end of Season One. Thanks for listening. We've managed to cover a lot in this series but there's still plenty more to learn from our guests. If you go to directionspodcast.com.au, you can find lots more resources.

You can also register your interest to participate in some follow-up forums with our guests, where you can ask all your questions. Find a link in the episode notes or go directionspodcast.com.au and keep an eye on your podcast feed for more bonus episodes of Directions.

This is a Boustead Geospatial Technologies production. This episode was the narrated by me, Stan Grant and Brian Boulmay. Sound engineered by Nearly Media and Deadset Studios with editing support from Kim Douglas and Sydney Podcast Studios.

Artwork by Superscript. And our executive producers are Alicia Kouparitsas and Raquel Jackson. If you like our show, please give us a five-star rating. Leave a review and be sure to tell your friends. Follow us on Apple podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also download a free trial of Esri software, check out our show notes and access other resources at directionspodcast.com.au.

The views and opinions expressed in this podcast are solely those of the participants and do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of Esri Australia, its subsidiaries or partners.

Hypothetical scenarios presented as part of this episode are purely fictional, and while they may draw on current issues, they do not depict the actions, values, or beliefs of any specific individual and or organisation.

And finally, this production would not be possible without the support of Esri Australia.

VIEW TRANSCRIPT

VIEW TRANSCRIPT